PHOTO

On Oct. 10, 2010 Arab and African leaders descended on Sirte, a coastal city in Libya, for an Afro-Arab Summit presided over by Muammar Gaddafi. Six Arab leaders lined up for a group photograph that, nine years later, would make the rounds on social media, altered by the addition of a red “X” over the images of all six: Tunisia’s Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Yemen’s Ali Abdullah Saleh, Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi, Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, Algeria’s Abdelaziz Bouteflika and Sudan’s Omar Al-Bashir.

A few months after the photo was taken, a moment of reckoning came in the form of the “Arab Spring,” which toppled four of the six leaders within a year of the summit. The other two — Bouteflika and Al-Bashir — eventually succumbed in April this year to protests demanding an end to their combined 50 years of rule. Yet, even as the Sudanese and Algerian peoples celebrate the downfall of those who were once “untouchable,” a pervasive anxiety remains:

This region, the Middle East and North Africa, is not particularly good at revolution. In fact, even after the 2011 uprisings that installed four new governments and inspired protests in other seemingly “stable” Arab states, only Tunisia was able to eke out some sort of meaningful change. At times, even that small progress came under intense pressure as new players vied to shape the narrative and claim ownership of the country’s lurch towards democracy.

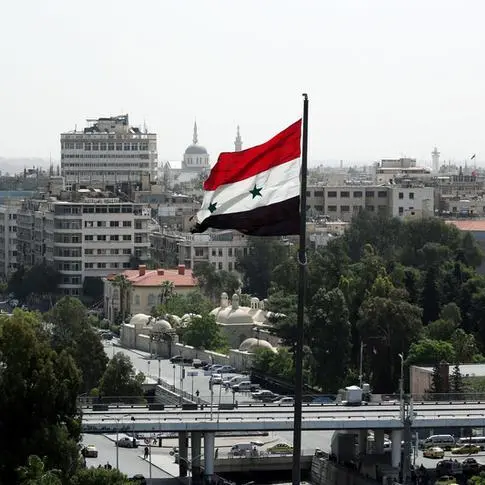

Libya, Syria and Yemen descended into civil war, while Egypt's parliament recently voted to grant President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi the chance to stay in power for another decade, effectively making him Mubarak II.

In Algeria, close allies of Bouteflika ascended to the leadership; officially so, that is, given that they were already functioning as the head of state when the former president was too sick to perform his duties. The country’s moment of awakening was quickly whittled down, as of now, to what amounts to a minor change to the status quo.

In the case of Sudan, even though 30-year incumbent Al-Bashir was eventually overthrown, a military council headed by his defense minister/vice president and the head of the armed forces, Awad Ibn Auf, attempted immediately to take over.

Libya, on the other hand, is a peculiar case. Unlike Algeria and Sudan, where protesters gathered under one banner to demonstrate peacefully and force a singular outcome, Libya's quest to depose Gaddafi went awry. It is likely that the tense situation in the North African country will persist, given the numerous heavily-armed, well-financed, non-state actors still active there with conflicting aims.

Compared with Algeria and Sudan, the dynamics in Libya are very different. The structures that protests might target as a means to pressure those in power are largely non-existent. More than that, civilians are caught in the crossfire of competing interests, lawlessness, a hobbled UN “peace/transition” process and unfettered foreign military support, as well as extremist elements that prey on the chaos to spread their roots, further entrenching the status quo.

Fortunately, there are glimmers of hope for the futures of Sudan and Algeria at least.

When the Sudanese people successfully ousted Al-Bashir, the protesters were not content with a “transitional” military council with strong ties to the toppled regime dictating the way forward. As a result, Ibn Auf quickly resigned following further intense protests, leaving Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman Burhan — the army's inspector-general — to succeed him. This appeased the protesters since he had sided with them during the initial sit-ins that led to Al-Bashir’s downfall.

This was just the beginning a complete transformation of a political system that had languished under authoritarian rule for 30 years. Protesters had learned from the experience of northern neighbor Egypt about the dangers of allowing a military-controlled transition. It is also likely they had a keen eye on the parallel developments in Algeria, where “le pouvoir” (the power) was still dictating terms even after Bouteflika's resignation.

Sudan's civilians have orchestrated the removal of Salah Gosh — Al Bashir's intelligence and security chief; Ibn Auf is no longer the defense minister, and three of Sudan’s top prosecutors were sacked. The former interior minister and the head of the former ruling party, the National Congress Party, face charges of corruption and have been implicated in the deaths of protesters. The NCP has been denied any chance to participate in the transition process.

While Sudan’s elites have quickly initiated and underscored the sweeping changes to the political system, their Algerian counterparts have not been as receptive. However, the lessons from 2011’s failed “revolutions” are still fresh in people’s minds and protesters remain determined not to fall into the same traps as other countries in the region. Fortunately, Sudan has leaped ahead to demonstrate how to upend an entire political system to place power in the hands of the populace.

Although Bouteflika ultimately resigned, peaceful protests continued demanding the resignations of the “3Bs:” Prime Minister Noureddine Bedoui; speaker of the uppper chamber of Algeria’s parliament, Abdelkader Bensalah; and head of the Constitutional Council and Army Chief of Staff Tayeb Belaiz. A the time of writing, the unrelenting protests had forced Belaiz to tender his resignation, which is likely to intensify the pressure on the remaining two to also step aside.

Although it came eight years late, if Sudan and Algeria manage to successfully transition to stable, civilian-led democratic governments, they will join Tunisia as the “success” stories of the Arab Spring.

Libya, on the other hand, stands at the precipice of a bloody, all-out civil war. Eight years of chaos have wrested power from the people, leaving the future of the nation to the purview of military men, militias and the gamesmanship of bad-faith foreign powers.

The experiences of all three countries, however, demonstrate the deep challenges and risks of political change in the Arab World, where it might be relatively easy to throw everything up in the air, but no one can quite know for sure where the pieces will land.

• Hafed Al-Ghwell is a non-resident senior fellow with the Foreign Policy Institute at the John Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. He is also senior adviser at the international economic consultancy Maxwell Stamp and at the geopolitical risk advisory firm Oxford Analytica, a member of the Strategic Advisory Solutions International Group in Washington DC and a former adviser to the board of the World Bank Group.

Twitter: @HafedAlGhwell

Copyright: Arab News © 2019 All rights reserved. Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (Syndigate.info).