PHOTO

(The author is a Reuters Breakingviews columnist. The opinions expressed are her own.)

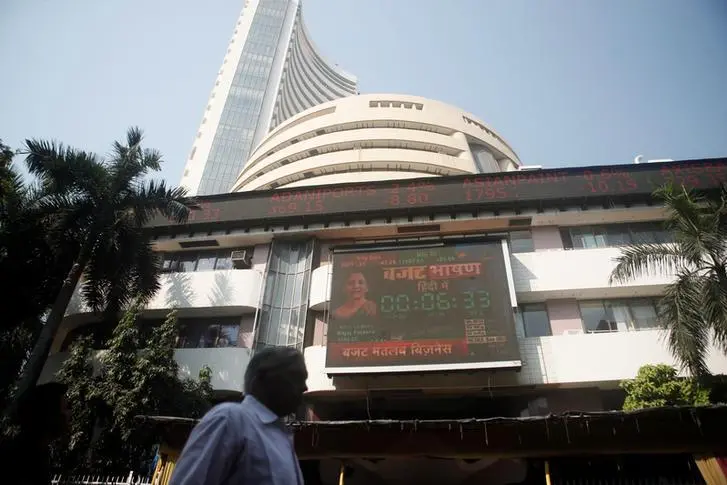

MUMBAI - India is on the verge of squeezing its most exciting companies too tightly. Policymakers promised to tweak existing rules to allow local companies such as SoftBank-backed 9984.T Paytm and online insurance marketplace PolicyBazaar to list overseas, but now may force them to sell shares on a domestic bourse simultaneously or soon after. It is a clumsy, heavy-handed idea.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government might be inspired by China’s efforts to woo overseas-listed homegrown champions to return to domestic boards. Policy changes have encouraged e-commerce titan Alibaba and others to come back to Hong Kong and mainland exchanges with secondary listings; others have abandoned New York entirely. Some local firms are choosing to debut on Shanghai’s new STAR board. Washington’s intensified scrutiny of U.S.-listed Chinese companies is a factor, but so are relaxed rules.

It’s easy to see why India’s policymakers want to keep companies at home. For one thing, it would mean businesses such as Reliance Industries’ Jio Platforms and Reliance Retail businesses, already valued in private investments at $70 billion and $57 billion, respectively, might allow mom-and-pop investors share in wealth creation. Relatively shallow local capital markets also would get deeper: Indian bourses had a market capitalisation of $2.2 trillion in 2019, roughly a quarter of China’s. And investors have been happy enough so far to award frothy valuations.

The availability of foreign listings need not crowd out India’s markets, however. Smaller start-ups such as online food-delivery firm Zomato, valued at $3.3 billion, might prefer to stay at home having watched plenty of mid-sized U.S.-listed Chinese stocks become orphaned, ignored by analysts and investors unsure about foreign quirks. What’s more, India might accelerate interest in its own capital markets if a few large companies successfully fly the saffron, white and green flag overseas.

One danger is that if India forces companies to go public domestically, startups will incorporate in Singapore and elsewhere to avoid being subjected to such rules later in life. And more mature companies could decide to stay private longer, waiting until they become less risky in the eyes of local investors. New Delhi would achieve more for its tech industry by keeping a looser grip.

CONTEXT NEWS

- Indian companies that list overseas will have to subsequently go public on a domestic bourse under policy changes being considered by government officials, Reuters reported on Sept. 13, citing unnamed sources.

- India said in March it would allow local companies to list abroad directly but the rules have yet to be set. Only certain types of securities, such as depository receipts, are currently allowed to be listed in foreign markets, but only after a company goes public in India first.

- Under the new rules under consideration, companies would have between six months to three years to list shares in India, Reuters reported. The rules are being drafted by the finance and corporate affairs ministries and will be finalised later in September, it added.

(The author is a Reuters Breakingviews columnist. The opinions expressed are her own.)

(Editing by Pete Sweeney and Jamie Lo) ((una.galani@thomsonreuters.com; Reuters Messaging: una.galani.thomsonreuters.com@reuters.net))