PHOTO

The UAE announced that it had passed a federal debt law in October last year, and providing a benchmark yield curve for dirham-denominated debt was one of the reasons given by the governor of the central bank for passing the law.

Speaking at a media roundtable launching a white paper on the MENA debt market held at Nasdaq Dubai's headquarters on Monday, Emirates NBD Asset Management's director of fixed income, Parth Kikani, said: "I think the local currency issuance could be very interesting.

“With this law being passed in the UAE, you could see more local currency issuance in the UAE. So the government forms a local currency curve and the corporates can borrow based on the local currency curve of the government. Since the corporates have local dirham-denominated revenues, it is better for them to borrow in dirham(s).”

When asked how long it would take for a yield curve to be formed, Kikani said: “About one or two years if they start issuing (bonds) regularly.”

He pointed out that Saudi Arabia had begun a programme of issuance in its domestic currency, the Saudi riyal (SAR), in 2017, issuing five, seven and 10-year notes both in 2017 and 2018.

“You have roughly six or seven issuances in the local currency. That is six - at least - points on the curve. So if you have a Saudi corporate who wants to issue in SAR, they at least have a curve outstanding from where they can price their risk.”

Of the $84 billion in hard currency bonds issued in the MENA region in 2018, $28.2 billion came from UAE-based entities, making it the third-biggest market behind Saudi Arabia ($32.4 billion and Qatar ($29.1 billion). Kikani forecast that in 2019, “we should see the same amount, similar to last year of about $28-$30 billion of bonds issued in the UAE”.

Although he predicted a balanced budget for the UAE this year, meaning issuance from sovereign entities is not likely to be high (other than a potential refinancing by Abu Dhabi’s government of bonds that are due to mature this year), Kikani said he expects more activity in the bond market from corporate issuers.

“We have seen more corporates come to the market last year as we saw first time issue from Senaat," he argued. "This year, as we see Expo 2020 activity pick up, we will see a more diverse set of issuers accessing the capital markets to raise funds.”

Currently, the United Arab Emirates does not raise debt at a federal government level, but emirates tap debt capital markets individually. A paper published by S&P Global last month on MENA sovereign ratings showed that Abu Dhabi enjoyed the strongest rating from the agency (AA), followed by Ras Al Khaimah (A) and Sharjah (BBB+). The Dubai government does issue bonds, but these are unrated. The government of the emirate of Ajman also told Reuters in December that it plans to issue its first dollar-denominated bonds this year.

Rating required

Kikani said that the UAE would want a rating at a federal level to issue dirham-denominated bonds. “It is always better to get a federal rating so that investors, not only the local but also international, can also benefit from investing in the local currency.”

Kikani, who manages Emirates NBD Asset Management's MENA Fixed Income Fund, said that the fund was 'overweight' UAE bonds and Qatar bonds, describing the latter as having an “attractive risk premium”. It is underweight Oman bonds, given the need for reforms to reduce the country’s fiscal benefit.

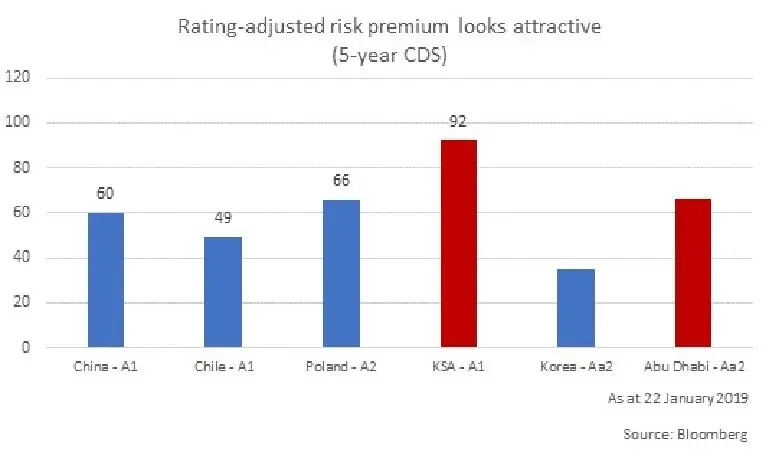

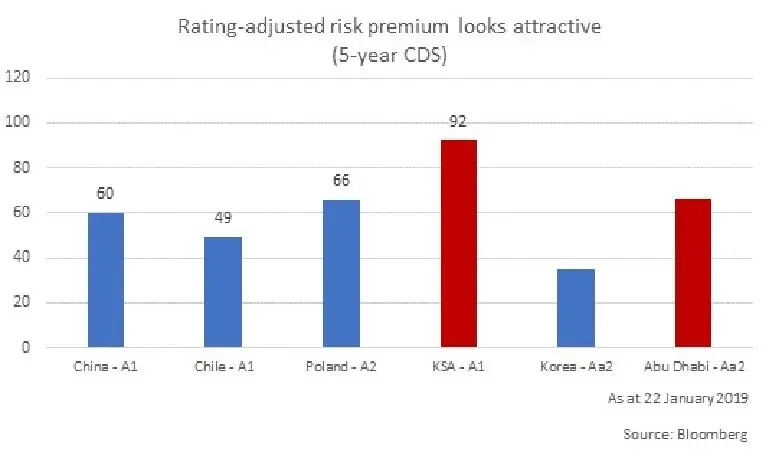

The white paper, which was co-produced by Emirates NBD with Swiss fixed income specialist Fisch Asset Management and Kuwait's KAMCO Investment Company, stated that bonds from the MENA region generally carry a higher risk premium than other emerging market bonds that have the same credit rating. This was attributed to a number of factors, including geopolitical uncertainty, a continued reliance on oil as a source of government revenues, and a wave of new supply issued by Middle East entities.

As of 22 January, for instance 5-year credit default swaps on Saudi Arabia's A1-rated sovereign bonds were priced at 92 basis points (bps), while China's A1-rated sovereign bonds were priced at 60bps and Chile's at 49bps.

Kikani said that as the GCC bonds begin their weighted inclusion into JP Morgan's emerging bond indices, which begins on Thursday and continues until the end of September,

“we will see more international investors looking at the region, and this excess risk premium that we have compared to other emerging market players, will reduce”.

Philip Good, CEO of Fisch Asset Management, said that emerging market corporate issuers typically continue to trade at higher risk premia than very similar U.S. or European corporate bonds in the same industry, with the same credit rating, adding that sometimes it can take 10 years for this gap to converge. However, he argued that a slightly higher risk premium can be more attractive in investors’ eyes.

“As long as you have this higher premium and you perceive it as the same credit risk, that's good. You get compensated for it.”

(Reporting by Michael Fahy; Editing by Mily Chakrabarty)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Disclaimer: This article is provided for informational purposes only. The content does not provide tax, legal or investment advice or opinion regarding the suitability, value or profitability of any particular security, portfolio or investment strategy. Read our full disclaimer policy here.

© ZAWYA 2019