PHOTO

(The author is a Reuters Breakingviews columnist. The opinions expressed are her own.)

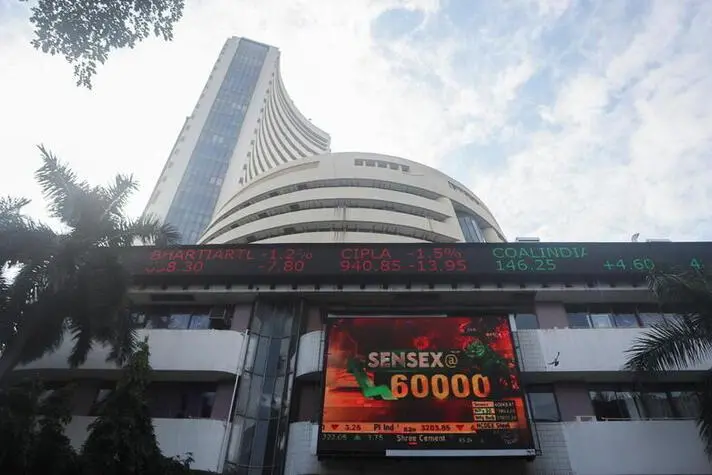

MUMBAI- Anchor, kitchen sink, fire engine, shock absorber, mop, buyer of last resort. These are just some of the unflattering descriptors used by Mumbai financiers to describe state-owned Life Insurance Corporation of India, its $500 billion of assets and the unusual government-directed role it plays in the country’s capital markets. Just exactly how, and whether, that will change after its blockbuster initial public offering is one of the big questions for both New Delhi and new investors alike.

LIC is quite literally everywhere. It boasts some 290 million policyholders, roughly equal to the number of households across the country. An army of 1.3 million sales agents live in big cities, small towns and far-flung mountain villages. They’re often the first port of call for any Indian who scrapes together a bit of money to park somewhere. LIC insures everyone from fund managers to domestic helpers.

The brand became powerful thanks to a 40-year-plus monopoly, until the life insurance market was opened to private competition at the turn of the century. LIC has since ceded a big slug of its share, but it retains a 64% hold on gross written premiums.

Executives, regulators, and bankers from 10 firms, including Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, Bank of America and JPMorgan, are preparing LIC's gigantic share sale. It might seek to raise some $10 billion assuming its sole owner, the government, offloads 5% at the upper end of a widely anticipated $200 billion market value. That would be four times the record set by Paytm-owner One 97 Communications in November, which has traded abysmally since.

Large investments from global sovereign wealth funds should help get the LIC deal done, possibly in multiple tranches, but that is likely to leave smaller pools of capital available for any IPOs that follow in the coming months. In terms of national significance, however, the transaction is on a par with the listings of oil giant Saudi Aramco to the Gulf kingdom in late 2019 and British Telecom to the United Kingdom in 1984.

Selling a chunk of the insurer is Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s high-stakes move to tap the government’s largest store of wealth beyond the Reserve Bank of India’s so-called capital surplus, which bureaucrats occasionally raid. Although the tea-seller turned politician successfully struck a deal last year to offload debt-laden national carrier Air India to the Tata group, New Delhi routinely undershoots its budgeted target to raise money from asset sales.

Such shortfalls were disappointing before the pandemic struck, more so during the subsequent equity market bull run. Now it represents a growing risk to the government’s creditworthiness. The health crisis crimped revenue and forced additional spending. General government gross debt topped 90% of gross domestic product in 2021, per International Monetary Fund estimates. Trimming borrowing would help keep a lid on the bond yields that determine how much the country pays on its dues as the U.S. Federal Reserve plots interest rate hikes and funds flow out of emerging markets. That would shore up India’s financial credibility as it woos foreign manufacturers and more. Politically speaking, shoring up the country’s finances also could help Modi lay the groundwork for any spending uptick ahead of national elections, expected in 2024.

Even so, it will be a slog to get the LIC deal across the finish line. Valuing the company and its hodgepodge of holdings is a gargantuan task for the appointed adviser. It’s the largest investor in the local stock market, owning 6% of Mukesh Ambani’s $225 billion Reliance Industries and 4% of $190 billion IT giant Tata Consultancy Services. It also has large stakes in India’s lenders, including IDBI Bank, after LIC stepped up in 2018 to help with a bailout.

While the government will keep one eye on pocketing needed proceeds, it also knows it will have to leave enough value behind so that LIC’s shares can have a steady performance in secondary trading. The task is even more important than usual because individual policyholders will be allocated a portion of the deal, a bold move that will bring millions of new investors to India’s stock market. Getting money out from under mattresses and away from gold and into equities and other securities is a helpful trend that has been accelerating during the pandemic.

For valuation purposes, $60 billion State Bank of India is instructive. Despite being held in similarly respectable regard, it trades on 1.5 times book value, half the multiple of its larger private sector rival, HDFC Bank. One reason is that it’s a government-controlled entity and is used to drive policy, often at the expense of shareholders. A further discount might be warranted for LIC because insurance rivals such as SBI Life and HDFC Life have a more modern sales model, relying on partner banks and digital channels that can more easily reach India’s young urban population who will drive growth.

SBI’s track record also suggests there are limits to how much the scrutiny from a public listing can help improve efficiency and corporate governance. It moved to absorb five of its subsidiaries in 2016 without seeking shareholder approval, a decision that helped the government make progress on its aim of consolidating the banking industry. SBI also was nudged by authorities into leading a 2020 rescue of Yes Bank that has not generated much value.

There might be some benefits, though. For example, if a significant chunk of households end up owning LIC shares, the government is likely to be a little more cautious about how much it asks of the insurer. That, in turn, might force New Delhi to consider more market-led solutions for financial institutions that run into trouble or for those it wants to offload. It could even make it easier for officials to privatise more lenders, a wish-list item for many international investors.

Keeping LIC’s investment portfolio in good shape also would help ensure that politicians can keep selling down its stake in the insurer to cover future budget shortfalls or to fund projects to support economic growth. There are great risks in taking LIC public, but Modi seems to have calculated them well.

(The author is a Reuters Breakingviews columnist. The opinions expressed are her own.)

(Editing by Jeffrey Goldfarb and Katrina Hamlin) ((For previous columns by the author, Reuters customers can click on GALANI/ SIGN UP FOR BREAKINGVIEWS EMAIL ALERTS https://bit.ly/BVsubscribe | una.galani@thomsonreuters.com; Reuters Messaging: una.galani.thomsonreuters.com@reuters.net))