PHOTO

Joe Biden's first year in office could go down in history as a record-breaker on the job-creation front, with an explosion in hiring expected as the coronavirus vaccine rollout allows Americans to emerge from a year in hiding.

It may not be enough.

Only slightly more than half of the 22 million jobs lost in the pandemic were regained by the end of last year. Even if 2021 hiring shatters the post-World War Two record of 4.27 million jobs created in 1984, roughly a quarter of those who lost work could still be on the sidelines, with bleak prospects for regaining their vocations in an economy reshaped by the pandemic.

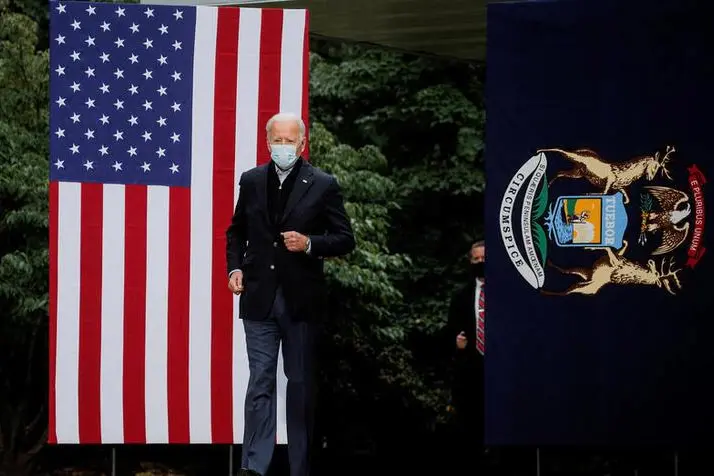

As Biden takes the oath of office on Wednesday, the job market awaiting him presents a monumental challenge.

Just a year ago, a record-long expansion was creating more opportunities and higher pay for women, minorities and other workers on the margins. These same groups - key to his election victory - were disproportionately harmed by pandemic job losses in service-sector jobs that face the longest road to recovery.

"It's not only about recouping what we've lost, it's recouping what could have been," said Diane Swonk, chief economist for Grant Thornton. "You need a lot of tail wind to get there."

Biden unveiled an ambitious $1.9 trillion plan last week for shoring up the economy by enhancing jobless benefits and providing more direct cash payments to households. A second phase of his plan is expected to boost job creation through investments in infrastructure, clean energy projects and education. It is unclear how many of his proposals will pass through Congress, but Democrats' slim majority in the Senate may help.

Janet Yellen, the former Federal Reserve Chair and Biden's nominee for Treasury Secretary, urged lawmakers on Tuesday to act aggressively. "Without further action, we risk a longer, more painful recession now — and long-term scarring of the economy later," Yellen said during her confirmation hearing.

That fiscal support, if delivered, could be bolstered by another tailwind: Easy monetary policy from the Fed.

Fed officials committed last year to a new framework that aims for "broad-based and inclusive" employment. Under the new approach, policymakers will no longer raise interest rates preemptively when the labor market is heating up in anticipation of faster inflation. Instead, rates will stay low for longer, giving the economy more time to benefit disadvantaged workers.

"They're going to keep their foot on the accelerator even beyond the time when we’re at full employment," said Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. Combine that with additional fiscal support, and you suddenly have "a lot of policy juice to the economy," he said.

PAIN UNEVENLY SPREAD

It took more than six years for the U.S. labor market to recoup all of the jobs lost during the last recession. Policymakers are expecting the recovery to happen more quickly this time around with the help of effective vaccines.

But as the post-pandemic jobs landscape takes shape, some workers may need extra help moving into different lines of work.

Special attention may need to be paid to the 4 million Americans who have been out of work for more than six months, putting them at greater risk of facing pay cuts or dropping out of the labor force altogether. In their ranks: Many of the servers, cooks, bartenders and other leisure and hospitality workers left jobless by the shutdowns meant to curb the virus.

"Unless we act now, we're going to again leave behind millions of Americans," said Senator Chris Van Hollen, one of several lawmakers who met virtually last week with Cecilia Rouse, Biden’s nominee for chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, to discuss programs that could help the long-term unemployed.

The low-wage workers hit hardest by pandemic job losses - including women, Black and Hispanic workers - are also among those at greater risk of falling through the cracks as the economy heals.

"Even though by next year the economy should be booming, it still is going to take quite a while" for Black and Latino workers to see labor market gains because they are more subject to discrimination, said William Spriggs, chief economist with the AFL-CIO, the largest federation of U.S. labor unions.

For instance, the unemployment rate for white workers dropped to 6% in December, below the overall unemployment rate of 6.7%. But Black and Hispanic workers faced higher jobless rates of 9.9% and 9.3%, respectively.

Many women are also at risk of facing lasting scars after being disproportionately affected by shutdowns of schools and child care centers. Of the 3.9 million people who dropped out of the labor force between February and December, 55% were women.

Bringing them back to work will require policies that make caring for children and other relatives more affordable, said Kathryn Anne Edwards, a labor economist for the Rand Corporation.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said last week that he is hopeful the labor market may surpass pre-crisis levels soon.

"We’ve got to get through this very difficult period," he said on Thursday during a virtual event organized by Princeton University. "But as the vaccines go out and we get COVID under control, there’s a lot of reason to be optimistic about the U.S. economy.”

(Reporting by Jonnelle Marte; Editing by Andrea Ricci) ((Jonnelle.Marte@thomsonreuters.com; +1 646 978 0908;))