PHOTO

The record levels of gold buying by central banks which bolstered the price of the yellow metal in 2018 has continued into the first couple of months of 2019, with 51 tonnes bought in February alone.

Speaking at the Dubai Precious Metals Conference earlier this month, Ross Norman, CEO of London-based gold bullion broker Sharps Pixley, said that demand from central banks in January and February “amounted to 90 tonnes of fresh buying”, which is 61 percent higher than the 56 tonnes bought in the first two months of 2018, and the highest rate of growth since the first two months of 2008.

“On a pro-rata basis, we would expect demand to be in the order of 540 tonnes for this year if this remains consistent. That's about a 20 percent decline only from the records that we saw last year,” Norman said.

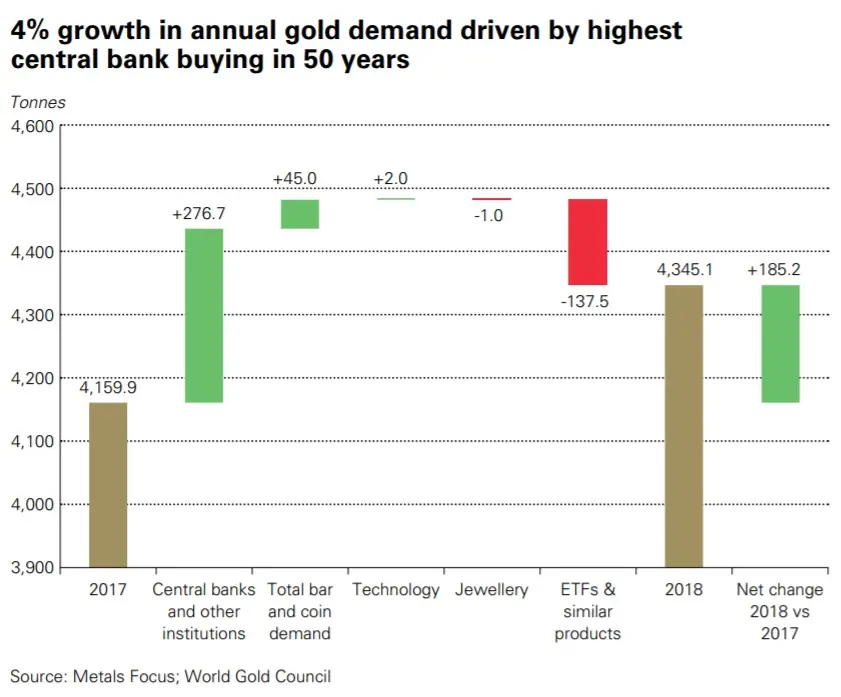

In 2018, central banks bought 651.5 tonnes of gold, which was the highest level of demand seen since the United States ended the convertibility of dollars for gold in 1971. This helped to push overall gold demand for 2018 higher by 4 percent to 4,345.1 tonnes.

“It would be tempting to ask ourselves what the central banks know that we don't,” Norman said. “The reality is central banks are buying an awful lot of everything. They may have acquired somewhere in the region of $446 billion in gold over the last 10 years, but actually they have been buying an awful lot more of other stuff, whether it's equities, indices or bonds.”

Shaokai Fan, central banks and public policy director for the World Gold Council, told the conference that prior to the global financial crisis of 2008, “central banks were mostly net sellers”, with European banks typically offloading around 100 tonnes per year.

“That all changed after the financial crisis when the western banks stopped selling, but the emerging market banks really started buying significant amounts of gold,” Fan said, noting that the current buying spree was led by Russia, China and Kazakhstan. This has since widened, however, with European nations such as Poland and Hungary becoming significant buyers.

“Beyond that, we've also seen India as a major buyer. They've been active now I think for the past 14-15 months, buying steadily every single month,” Fan said. “Also last year, we saw Iraq from this region buying gold—six and-a-half tonnes. We saw South East Asia return to the gold market—between one and two tonnes each for Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines.”

Alexander Pschenichnikov, deputy head of department of state regulation in the Russian Federation’s Ministry of Finance, said that Russia has been buying more than 200 tonnes of gold every year since 2007-08, adding that the proportion of gold mined in Russia bought by the central bank has increased from around 3 percent of the total in 2008, to around 70 percent. The amount mined each year in Russia has also increased from around 270 tonnes in 2007 to more than 300 tonnes.

“(Also), if you look at the returns for 10 years, gold beat dollars and U.S. treasury bonds if you calculate it in roubles. For gold, it's about 14 percent. For US treasury bonds, it's about 13 percent.”

Chinese conundrum

Amid economic uncertainty and as China becomes a bigger part of the global economy, many countries are looking to ‘de-dollarise’ their economies. However, Chinese renminbi (RMB) remain difficult to source.

“That's largely because the Chinese capital account is closed,” Fan said. “It's relatively hard to get liquidity in RMB onshore, so I think that for central banks they are re-evaluating what their reserve portfolio should be.”

Gerhard Schubert, founder of the Dubai-based Schubert Commodities Consultancy, said that banks are also thinking about where their gold reserves are housed, given the Bank of England’s refusal in January this year to repatriate $1.2 billion worth of gold which it held as a custodian back to the Venezuelan government as countries began to de-legitimise the regime of leader Nicolas Maduro.

“There are behind closed doors a lot of conversations currently if the handling of the custodian request between the Bank of England and the Central Bank of Venezuela were handled right,” Schubert said. “All central banks are asking: ‘Could this happen to us?’

“The Bank of England is not the owner of the gold, it is purely the custodian. This is also one of the reasons why some countries are considering returning at least large parts, significant parts, from the Bank of England to their own countries,” Schubert said.

For instance, he said that Germany’s Bundesbank, which held most of its reserves at the U.S Federal Reserve until around five years ago had “removed a lot of its gold from New York back home”.

He said that by the end of 2020, it will have repatriated around 75-80 percent of its gold holdings.

Schubert said this trend towards repatriation was spreading globally and saw an opportunity there for the UAE.

“I can easily imagine the UAE as, let’s say, like the Switzerland of the Middle East, could become a hub for governments to store part of their gold reserves.”

Global uncertainty is also playing a role in gold buying among institutions, with Sharps Pixley’s Norman stating that institutional investors currently have 2,483 tonnes worth of gold accumulated via holdings in exchange-traded funds, which is the highest amount in six years.

“There's some evidence to suggest that there is some institutional buying that is propping up this sector,” he said.

Demand for gold jewelry was virtually unchanged last year at 2,200 tonnes, down by just one tonne on 2017, according to WGC figures. Demand for gold bars and coins increased by 4 percent, driven by higher coin sales. Demand for gold bars was steady at 781.6 tonnes, but gold coin demand reached a five-year high of 236.4 tonnes.

Demand varied widely across regions, though. Some 40 percent of all gold purchased last year was bought in India and China, and Norman said that in Europe, where his firm is one of the biggest sellers of gold bars and coins “sentiment towards gold in the retail sector is probably the worst for 20 or 30 years”, despite concerns about the economy.

Norman gave an upbeat forecast for the price of gold, despite the fact that it has traded within a reasonably narrow band of between around $1.050 and $1,350 per oz over the past five years, and that it remains considerably below the $1,922 per oz reached back in September 2011. The spot gold price stood at $1,275.78 per oz at 0115 GMT on Tuesday.

Long term view

He set out a number of scenarios for gold, based on historic events. Over the long run, since the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates ended in 1971, gold prices have increased in value by 7.5 percent at a compounded annual rate, while over the 15-year period since 2004 the price increase has been marginally higher, at 8.5 percent. Over a 20-year period since 1999, gold has averaged a 16 percent year-on-year increase, Norman said.

“There's certainly some basis for saying that gold should, at the very minimum, maintain its long term run rate since 1971 of 7.5 percent (growth),” he said. However, he argued that the current market is “very resonant of what we saw in the late 1990s”.

“We have a contraction in the producer base, we have some despondency in the sector for lack of price performance—mainly in dollar term—and we have according volatility and a very flat price.”

Schubert also pointed out that although gold’s performance may not be considered to have been strong in dollar terms (gold declined in value by 1.5 percent against the U.S. dollar last year, according to Eikon data) it finished 2018 at a record high against 72 other global currencies.

(Reporting by Michael Fahy; Editing by Brinda Darasha)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Disclaimer: This article is provided for informational purposes only. The content does not provide tax, legal or investment advice or opinion regarding the suitability, value or profitability of any particular security, portfolio or investment strategy. Read our full disclaimer policy here.

© ZAWYA 2019