PHOTO

The recent governance issues surrounding the private equity arm of Dubai-based Abraaj Group came as no surprise to Ludovic Phalippou, an associate professor of finance at Oxford University’s Saïd Business School and the author of a book titled ‘Private Equity Laid Bare’.

Abraaj Group, the Dubai-based ‘growth markets’ specialist founded by Arif Naqvi, has generated unwanted headlines since a Wall Street Journal story broke in February stating that a group of investors into one of its funds had hired external auditors to ascertain why $200 million of funds that they had contributed had neither been invested by Abraaj or returned to them.

The story generated headlines in the financial press around the world, mainly because of the high-profile of the investors launching the probe, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the World Bank-owned International Finance Corporation.

Abraaj Group pointed out in a statement in February that the fund was “less predictable than that of a standard private equity fund” as finding mature healthcare businesses in growth markets was difficult. It also said that even though the terms of its agreement allowed it to retain any capital called from investors until it was deployed, it had agreed to return unspent money to investors in December 2017.

Despite this, the fallout has continued. The firm told Reuters last month that it had begun to free large investors from millions of dollars in capital commitments after deciding to suspend its latest fund, Abraaj Private Equity Fund VI. Reuters also reported that the firm has held early-stage talks about a potential sale of its investment management arm.

Speaking to Zawya on the sidelines of an event held by Oxford Said Business School in Dubai last month, Phalippou said: “When I read that (Abraaj Group story), I was not particularly surprised. I said, 'Yeah, you know this is actually legal’. This is what the LPA (limited partnership agreement) says. ‘I call the capital and if I actually didn't execute the transaction I don't need to return the capital’.”

Investor pushback

Phalippou, who has been critical of the industry’s lack of transparency, said that he did not wish to discuss the specifics of the Abraaj case, but added the most interesting fact about it was that “it seems that this investigation is shaped by investors, which is something new”.

“So what I can say as an academic is that 10 years ago this wouldn't have happened. Now we have investors that are aware.”

Phalippou said that the LPAs the general partners (GPs) that run private equity funds have drawn up for the limited partners (LPs) who invest give the former a huge amount of control, creating clear conflicts of interest.

“The bottom line is that the LPs are giving carte blanche to the GP. The GP can do anything they want,” Phalippou says. “And that makes me a bit nervous. So I've been saying that for a long time I think it's really a problem,” he says.

An example given is a private equity firm which buys a consultancy business as a portfolio investment. The fund manager can then employ the same firm to advise all of the other companies in its portfolio and set its own price for this work, regardless of the market price.

Any mutual fund or publicly-listed entity conducting such ‘related party transactions’ would need to ensure they are conducted on an ‘arms length’ basis, set fair market rates and would face scrutiny both from stakeholders and regulators, Phalippou points out. The same restrictions do not apply to the private equity industry, which is not as heavily regulated – although practitioners would point out that since industry heads repeatedly return to the same investors when raising funds, short-changing them would be counter-productive.

Yet the greater scrutiny being shown by investors over private equity managers’ use of their funds is perhaps a sign of the growing importance of the industry.

Billions raised

A Global Private Equity report published in February by Bain & Company stated that private equity firms raised $701 billion in 2017, marginally below the record-breaking $703 billion raised by the industry in 2016. This brought the total raised by private equity funds to more than $3 trillion over the past five years, according to Bain & Company.

Despite the high fees that investors pay (typically a 2 percent annual management fee on capital drawn down from investors, and a 20 percent share of any profits generated), private equity has been so successful at attracting investment because of participants’ claims of superior returns over other asset classes.

The Bain & Company report states that over a 10-year period until mid-2017, the median net returns from private equity investments by public pension funds stood at 8.5 percent, compared to 4.2 percent from public equities, 4.5 percent from real estate and 5.2 percent from fixed income.

Funds also often cite their own track record on past deals, typically using an internal rate of return (IRR) figure. Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, one of the world’s biggest private equity funds, cites a gross IRR of 25.6 percent from funds with at least 24 months of its activity since its foundation in 1976, for instance, compared to a return of 11.6 percent invested in the S&P 500 index (of the biggest U.S. equities) over the same period. Similarly, Apollo Global Management cites an IRR from its private equity funds of 39 percent since inception in 1990.

Yet Phalippou dismisses IRR as a “junk” figure, stating that it makes some big assumptions. The first is that managers typically pool returns from good and bad funds. IRR also assumes that all proceeds investors receive are then re-invested. Most importantly, though, a spectacular return early on in a fund’s life can lead to a very high IRR figure being generated, even if the size of the initial fund is insignificant.

He says that if fund performance is measured by net present value (i.e. measured in monetary terms), the industry only outperforms the S&P 500 index by 3 percent, according to a 2014 study. But, he adds, the S&P 500 isn’t an appropriate benchmark.

“Private equity invests in mid-cap and small cap and these are companies that also outperform the S&P 500 by a wide margin,” he says.

He cites a 2016 study authored by five CFA Institute members (L’Her, Stoyanova, Shaw, Scott and Lai) which stated that when appropriate risk adjustments (for leverage, size and sectors) are made to a benchmark equities index it found no outperformance by private equity buy-out funds.

“More and more people understand this evidence and I think that can explain a number of trends - like the trend of investors trying to go in-house (pension funds and companies setting up their own private equity and venture capital arms) or doing co-investments,” Phalippou said, as this allows investors to avoid the industry’s higher fees.

Understanding fees

Phalippou does say that progress is being made in terms of fee transparency, though. The Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA), the body set up to look after the interests of large investors into private equity funds, created a template in 2016 for firms to follow when reporting fee structures, expenses and how they calculate the profit (carried interest) generated, so investors can make accurate comparisons.

The ILPA said that by the end of 2017, more than 150 organisations had endorsed the template, including a number of GPs running the funds and LPs requesting the information.

Finally, the success of the industry in attracting such capital could also be a factor that suppresses future performance.

In a press release accompanying its Global Private Equity report launch, the global head of Bain & Company’s private equity practice, Hugh MacArthur, pointed out that an industry flush with cash was “both a blessing and a curse”.

“Funds have ample money to spend, but the competition for deals is fierce. With deals being done at record-high multiples, the right sort of diligence is more essential now than ever before.”

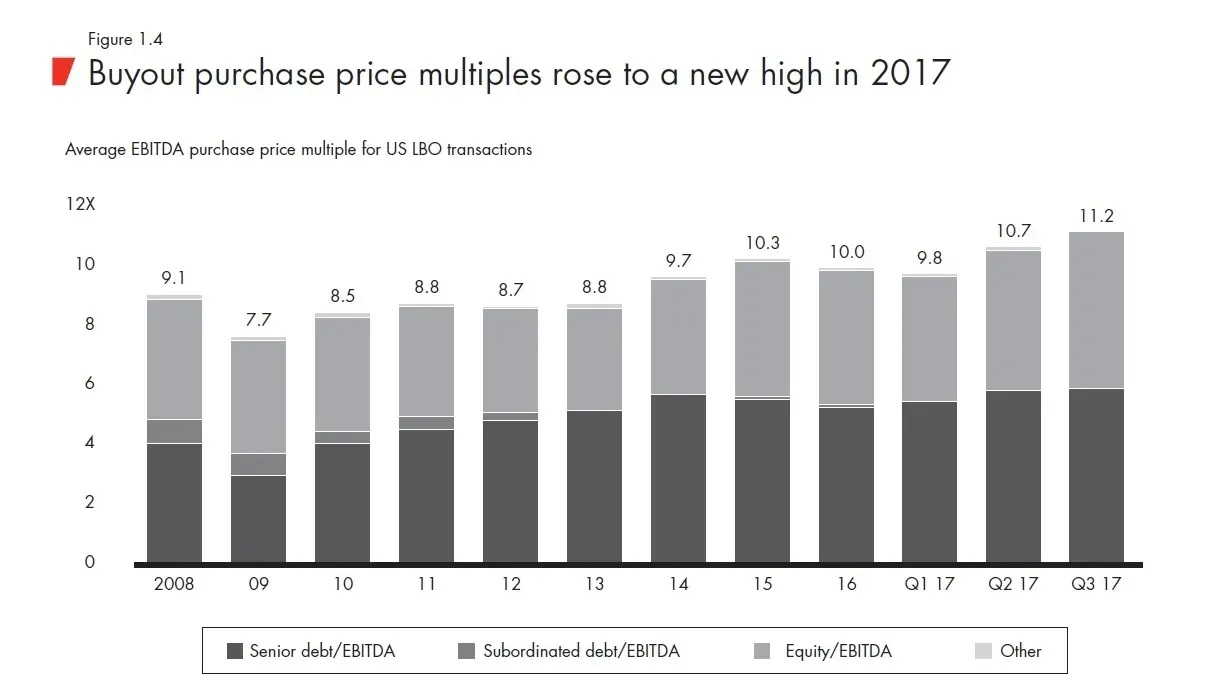

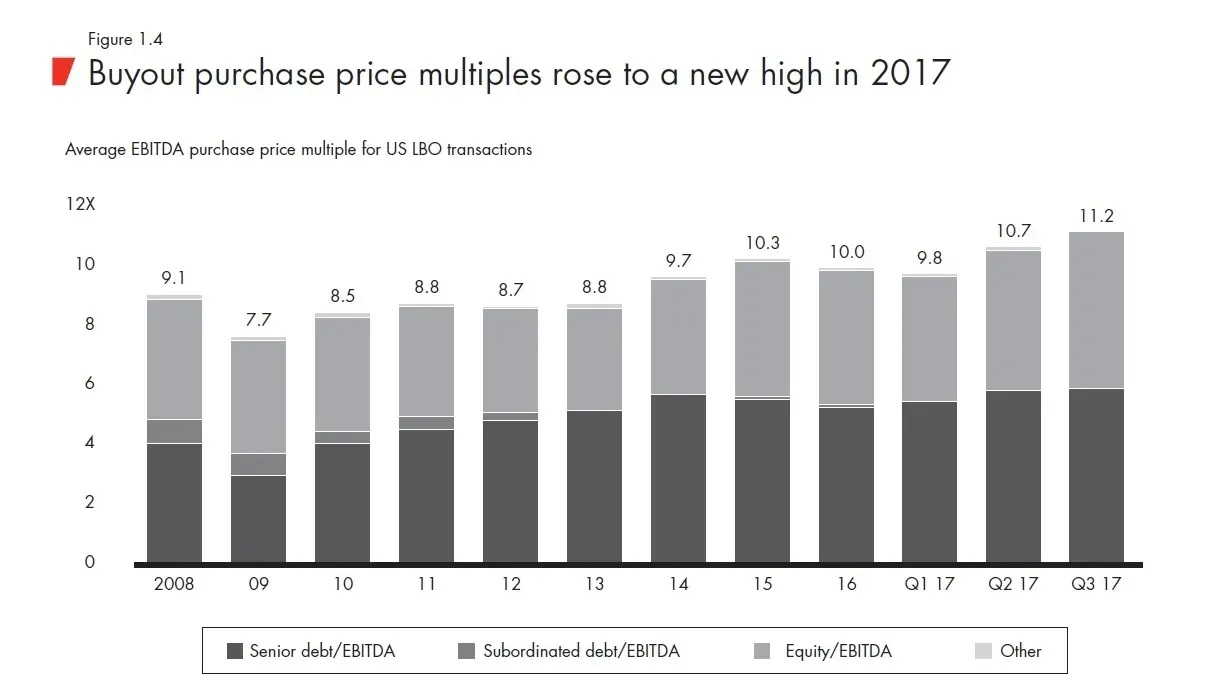

The amount of uncalled capital, or ‘dry powder’, at the disposal of GPs hit a record high of $1.7 trillion by December 2017, the report said. In the U.S. this has pushed up valuations of companies bought via leveraged buy-outs to 11.2x EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization), which is a new record.

In the run-up to the last financial crisis in 2008, buy-out firms were typically paying 9.1x EBITDA for businesses, but the Bain & Company report states that median valuations in the U.S. have been above 10x for the past three years.

Source: S&P Capital IQ Leveraged Commentary & Data; Bain & Company

A McKinsey & Co report published last month cited median EBITDA multiples for buy-outs of over 10x, which it said was “a decade high and up from 9.2 times in 2016”.

“With price tags now increasingly printed on gold foil, GPs had to be smarter with their investment decisions and more strategic with their choices,” it argued.

Phalippou said that he has been arguing that current buy-out prices are unsustainable for some time.

“I feel bad commenting on that because three years ago I wrote a big LinkedIn post on, like, ‘the crisis is going to happen because I've never seen such crazy prices’, and I'm defeated every year,” he said.

(Writing by Michael Fahy; Editing by Shane McGinley)

(michael.fahy@thomsonreuters.com)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Disclaimer: This article is provided for informational purposes only. The content does not provide tax, legal or investment advice or opinion regarding the suitability, value or profitability of any particular security, portfolio or investment strategy. Read our full disclaimer policy here.

© ZAWYA 2018