PHOTO

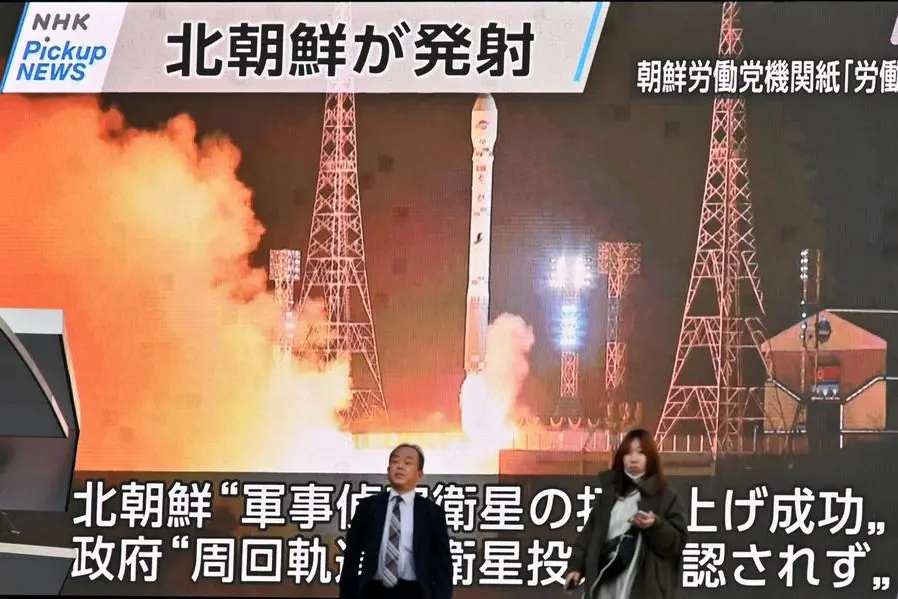

North Korea claimed Wednesday to have successfully put its first military surveillance satellite into orbit, with the South also preparing to send up its first spy satellite later this month.

The two launch attempts, set to come in such quick succession, appear to be the beginnings of a space race on the Korean peninsula.

Here, AFP takes a look at what we know about the new competition between the North and South:

Why does North Korea want the satellite?

North Korea first tried -- and failed -- to launch a satellite in 1998. In 2021, leader Kim Jong Un made developing a military spy satellite a key regime goal.

Pyongyang wants to monitor areas of strategic interest, including South Korea and Guam, experts say.

Real-time monitoring capacity "effectively means the advancement of preemptive strike capabilities", said Lim Eul-chul, associate professor at Kyungnam University's Institute for Far Eastern Studies.

Seoul and Washington have called the launches veiled ballistic missile tests, as space launch rockets and ballistic missiles have significant technological overlap, but different payloads.

However, if the North keeps launching satellites -- potentially even seeking Moscow's help to send some skyward from Russian spaceports -- it would indicate Kim is genuinely interested in space, said Cha Du-hyeogn, an analyst at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

"If North Korea repeats failures again and again, insisting only on domestic launches, that would suggest its main purpose is to improve ballistic missile performance," Cha added.

Did the launch work?

While Japanese officials have warned there is no evidence that Pyongyang's Tuesday night launch was indeed a success, North Korean state media claimed on Wednesday that Kim had reviewed images taken by the satellite of a US Air Force base in Guam.

"State-controlled media claims of a successful launch do not mean the satellite will actually perform meaningful reconnaissance functions," said Leif-Eric Easley, a professor at Ewha University in Seoul.

South Korea, which recovered debris from North Korea's previous failed satellite launches earlier this year, said they had no military value.

But Tuesday night's launch comes after a September meeting between Kim and Russian President Vladimir Putin, who suggested Moscow could help.

And Pyongyang has clearly improved since its last attempt, securing the engine thrust to stably lift a 300 kilogram payload into orbit, said Cha of the Asan Institute.

This can translate into direct military gains, giving the North "the capability to load nuclear warheads without excessive miniaturisation", he added.

So did Russia help?

Seoul has warned Russia is providing Kim with technical advice, in exchange for arms transfers for use in Ukraine.

Analysts say Russia's role appears to be mainly in the "software", given the short time span from the Kim-Putin summit to the third launch.

"If there had been a serious error to fix, such as a hardware change or a design change, a launch in November would have been physically impossible," said Chang Young-keun, a professor at Korea Aerospace University.

Cha of the Asan Institute added that if Russian engineers were involved, they would have helped with the launch coordinates, the stage separation point and know-how on assembling major parts.

"This proves that North Korea still has software problems -- in addition to hardware problems -- with its major weapon systems," he said.

What about South Korea?

South Korea does not have its own military reconnaissance satellites and relies on the United States to help it monitor North Korea's activities.

Seoul's finalised plan to put its own domestically built spy satellite into orbit was recently unveiled, with a launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket set for November 30.

If it works, it will be a huge boon for Seoul, experts say.

"Seoul will be able to independently obtain intelligence on North Korea's military trends that it previously obtained from the US and Japan," Ahn Chan-il, a defector-turned-researcher who runs the World Institute for North Korea Studies, told AFP.

Up until now, it has been "quite difficult" for the South to monitor North Korea "24 hours a day with US military assets alone", military analyst Shin Jong-woo told local media.

Experts say that having its own military spy satellite holds significant importance for Seoul, especially considering that North Korea enshrined in law the right to preemptively use nuclear weapons last year.

Is this a new 'space power era'?

South Korea sent up its first lunar orbiter, Danuri, last year on a SpaceX rocket. It also became one of a handful of countries to successfully launch a one-tonne payload using its own rocket last year.

The November 30 launch of Seoul's first homegrown military spy satellite from California's Vandenberg Air Force Base would "lay the foundation for opening a full-fledged space power era" for the country, Minister of Defense Acquisition Program Administration Eom Dong-hwan said in October.

The upcoming launch is part of Seoul's ambitious billion-dollar "425 Project", which aims to deploy five high-resolution medium- to large-sized military satellites into orbit by 2025.

North Korea, for its part, has also vowed to launch more satellites "in a short span of time" to step up its surveillance of South Korea, state media said.