PHOTO

There was a Monty Pythonesque flavor to the advice from the UK Department for International Trade that British companies exporting to EU countries set up separate businesses on the continent in order to circumvent the complex red tape, charges and taxes stemming from the Brexit agreement.

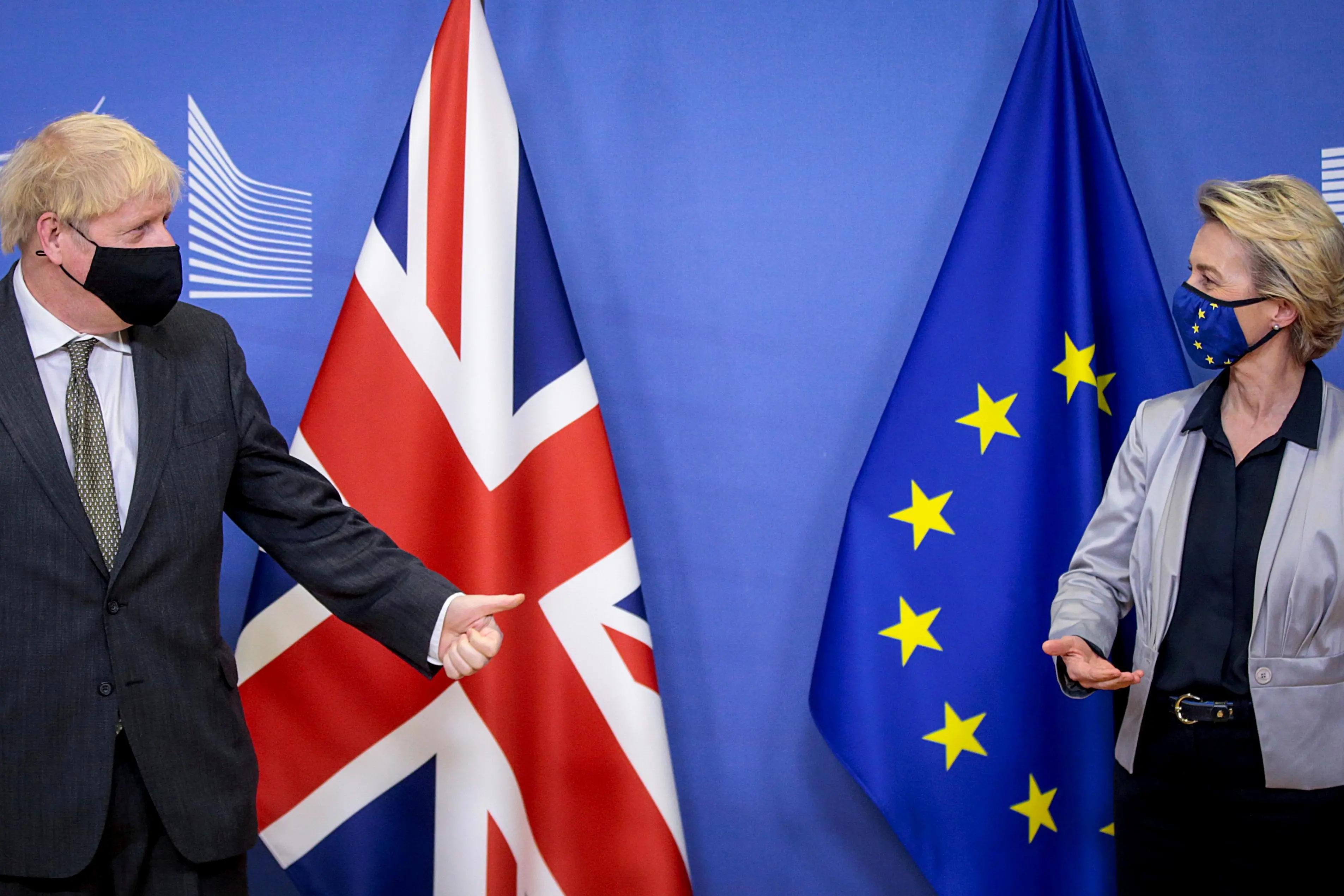

A month into Britain’s “independence” from the world’s largest trading bloc and second-largest economy, EU–UK relations have got off to a shaky start, and the first cracks are showing. The view that businesses will be better off by becoming European entities makes a mockery of the Brexiters’ argument, and particularly those of their leader, Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

Even before the ink dried on the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation agreement (TCA), signed on Dec. 30 last year, it was apparent that the agreement would be tested almost instantly, especially on the tricky question of Northern Ireland’s border with the Republic of Ireland. It was also unavoidable that the deep residue of resentment that remains between Brussels and London should surface within weeks as both became embroiled in a row over the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine supply. This highlighted the UK’s transformation from being an influential member of the EU to being a competitor, an opponent even, fighting over scarce resources.

In dealing with the horrendous consequences of the coronavirus pandemic, neither the EU nor the UK have covered themselves with glory. The levels of infection and mortality in this affluent part of the world make gloomy reading. But when it comes to the rollout of vaccinations the UK is way ahead of its European neighbors, even if it was the UK’s high mortality rate that pushed the Johnson government to bet on signing early deals with the companies developing vaccines. This has given Brexiters a sense of exoneration, almost of reprieve, and allowed them to claim that the EU lacks agility in dealing with crises such as the pandemic, and that its more powerful members are looking after their interests at the expense of the rest. Truth is, it was a case of manufacturing problems for AstraZeneca in Belgium and the Netherlands that slowed production and consequently supplies to EU countries, though the EU procrastinated and did little to ensure that it would be at the front of the queue for supplies of the vaccine.

This early clash between the EU and the UK will no doubt be resolved, but it has already exposed flaws in the TCA, highlighting its hasty implementation due to time pressure, and above all the negative consequences of Brexit. The agreement was signed two days before the previous interim arrangement was due to expire, forcing the EU and the UK to start the year trading under WTO rules, which was practically and psychologically a complete divorce that neither side wanted.

However, as the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier admitted, future trade friction over border checks on agricultural goods and the ban on chilled meat being exported from the UK to the EU were part and parcel of Brexit. It would have been optimistic to expect that such a radical change between two political entities would take place without glitches. However, the difficulties in moving goods and people caused by the pandemic, combined with new mechanisms that were put in place as a result of the UK no longer being part of the single market, created an almost perfect storm for a British economy that was already suffering from nearly a year of disruption.

It remains to be seen if both sides are ready to bury the hatchet after five years of tense and even hostile negotiations, and accept that they are destined to work together for the benefit of both. The first few weeks have shown, predictably, that the devil is in the detail, and the agreement has most certainly fallen short on coping with many of the issues involved in ensuring a smooth transition in EU–UK relations. This requires grown-up politics. It means, first, that the EU must get over its anger at the disruption and damage caused to the very idea and progress of the European project by Brexit and its fallout, and second, that the British government must forsake its populist approach to the EU as the organization to blame for its own shortcomings and everything that goes wrong in the UK.

Thus far, the messaging and the body language is leaning toward adversity and posturing rather than a wish to develop amicable and constructive relations. Downing Street’s refusal to give full diplomatic status to the EU’s ambassador to the UK, Jo?o Vale de Almeida, and his 25-strong mission has deeply upset Brussels, leading to the postponement of the inaugural meeting between the UK’s new head of mission in Brussels and EU officials.

Nevertheless, no issue epitomises the lingering friction between the EU and the UK more than the manner in which the Irish border issues are being handled, and for years to come this will serve as a barometer of EU–UK relations. Northern Ireland, for all intents and purposes in terms of free trade, was left by the TCA as part of the EU, with its invisible border with the Republic of Ireland and with no checks on goods moving between north and south. At the sniff of a disagreement over the supply of vaccines, the EU was quick to trigger Article 16 of the Northern Ireland Protocol, in other words to introduce checks at the border, signaling to the UK government that it has the means to pressure it and exploit its vulnerabilities in the post-Brexit era.

Faced with the UK leaving the EU, and moreover being the first country to do so, Brussels has felt it necessary to assert itself and demonstrate that there must be a heavy price. In the current global crisis caused by the pandemic this situation has become more acute, and the British government, and sadly its people, are starting to realize the cost of Brexit and its impact on daily life — but London and Brussels must recognise the importance of working together, both for each other’s benefit and that of the wider international community.

- Yossi Mekelberg is professor of international relations at Regent’s University London, where he is head of the International Relations and Social Sciences Program. He is also an associate fellow of the MENA Program at Chatham House. He is a regular contributor to the international written and electronic media. Twitter: @YMekelberg

Copyright: Arab News © 2021 All rights reserved. Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (Syndigate.info).