PHOTO

CAMBRIDGE – High among US President Joe Biden’s many priorities is reinvigorating an economy that – judging by the latest employment numbers – appeared to be slowing as 2021 began. Even if COVID-19 abates during the course of the year, and pent-up consumer demand kicks in, the United States faces immediate challenges in areas such as education, infrastructure investment, state and local finances, and especially the fight against the pandemic itself.

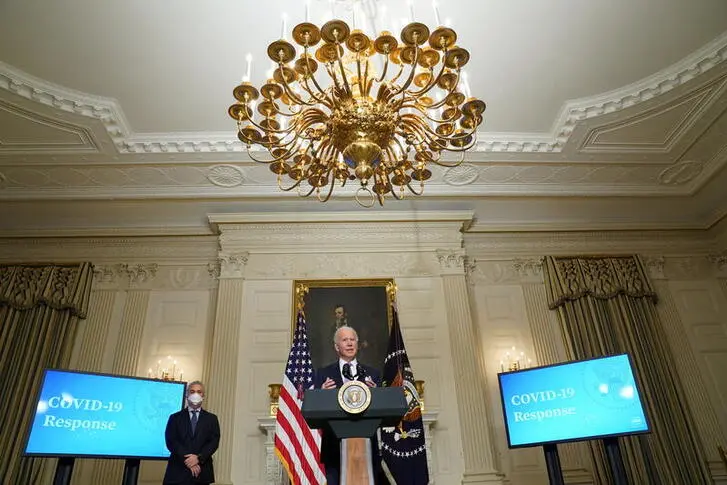

Biden has thus announced a $1.9 trillion “American Rescue Plan.” Moreover, he is rare among successful US presidential candidates in having stated honestly during the campaign that his spending would continue the recent trend of record budget deficits, notwithstanding his plans also to raise taxes on the wealthy. Most economists approve of this fiscal expansion, in light of America’s still-high unemployment, low inflation, and very low interest rates.

But with Donald Trump having departed the White House, many Republicans are suddenly rediscovering the dangers of budget deficits, after four years of conspicuous indifference. This was entirely predictable: for the last 45 years, the GOP has done the same thing every time a Democrat has held the presidency, and only then.

In fact, we can identify three long cycles, during each of which Republicans reversed their fierce opposition to deficits once they won the presidency: the 1980s, 1990-2008, and 2009-20.

In the late 1970s, Democratic President Jimmy Carter’s administration ran budget deficits, as most of its predecessors had done. Carter’s Republican challenger, Ronald Reagan, attacked the deficits in his 1980 presidential campaign and subsequent inaugural address. Even during a recessionary period, Reagan emphasized the urgent need to reduce the US national debt, then approaching $1 trillion, “beginning today.”

But once Reagan became president, he and the GOP-controlled Congress launched a three-year program of extensive tax cuts. And instead of offsetting the revenue loss by reducing spending, they increased the military budget. As a result, the US began to run record budget deficits.

These deficits tripled the national debt to $3 trillion by the time Reagan left office in 1989. But even after the US economy had fully recovered from the 1980-82 recessions, Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush – who accepted the GOP’s presidential nomination in 1988 with the famous pledge, “read my lips: no new taxes”– appeared unconcerned about the budget deficit. The national debt stood at $4 trillion when Bush left office in 1993, after a single term.

The second cycle had actually begun in 1990, when Bush abandoned his earlier pledge on taxes in reaching a budget deal with congressional Democrats to address the long-postponed deficit problem. This was the last time any Republican president has tried to live up to the label of fiscal conservative, and many in the GOP never forgave Bush for his tax apostasy.

Bill Clinton, a Democrat, did not campaign against the budget deficit in 1992, but once in office, he was persuaded to make fiscal responsibility a high priority. Yet, in 1993, congressional Republicans uniformly opposed Clinton’s “pay-as-you-go” (PAYGO) plan – a continuation of Bush’s post-1990 policy – which was to achieve a path of deficit reduction. (Under PAYGO, anyone wishing to cut a tax or raise spending must propose an offset somewhere else in the budget.) The Republicans predicted Clinton’s fiscal policies would result in slower growth and larger deficits, and continued to oppose them even as the 1990s economic recovery achieved historic length, with unemployment below 4% and budget surpluses by the latter part of the decade.

Bush’s son, George W. Bush, let the PAYGO provisions expire after becoming president in 2001. In that year and again in 2003, Bush Junior followed the Reagan playbook by enacting big tax cuts. He also increased federal expenditure during his first term, at four times the rate that Clinton had – not just on defense, but domestic spending as well. Even with unemployment down to 5% in 2005, Bush ignored warnings that running large budget deficits during an economic recovery would leave less fiscal space to respond to the next recession or crisis. Three years earlier, his vice president, Dick Cheney, reportedly said that, “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.” The national debt increased by another $4 trillion.

The third cycle began when Barack Obama took office in January 2009. A housing-finance crisis had induced a recession in December 2007, and by early 2009 the US economy was in its worst recession since the 1930s. Despite this, no Republican congressperson voted for Obama’s fiscal stimulus.

After regaining control of the House of Representatives in the 2010 midterm elections, Republicans succeeded in blocking continuation of the stimulus, even though the unemployment rate was still about 9%. The timing supports the view that the stimulus turned the economy around in the first half of 2009, and that its curtailment after 2010 slowed the subsequent recovery.

In the 2016 presidential campaign, Trump attacked Obama’s deficits, and said he would balance the budget “quickly” if elected. Trump even claimed to be able to eliminate the national debt.

But once in the White House, Trump followed the well-worn policy path of his Republican predecessors, securing passage of a tax cut in 2017 that overwhelmingly benefited the rich and was projected to cost $1.9 trillion over ten years. Spending increased, too, even though the economy was at the peak of the business cycle. The budget deficit surpassed $3 trillion in 2020 (more than double the previous record). The US national debt, at $27 trillion, is now set to exceed 100% of GDP for the first time since the end of World War II.

The US is now starting a fourth cycle. Given today’s record-low interest rates, all signs point to the desirability of large-scale federal borrowing to finance spending on worthy causes, ranging from defeating COVID-19 to investing in infrastructure and education. But Biden needs to act fast to ensure America’s economic recovery, because the Republicans, if true to form when out of power, will fight his spending proposals every step of the way.

Jeffrey Frankel, Professor of Capital Formation and Growth at Harvard University, previously served as a member of President Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers. He is a research associate at the US National Bureau of Economic Research.

© Project Syndicate 2021