PHOTO

One of the unintended consequences for the UK of the coronavirus crisis and Brexit has been that Boris Johnson’s premiership has involved very little international travel recently — and what there has been was mainly limited to Europe.

That will change in 2021, potentially dramatically, as he attempts to look beyond the continent to drive forward a new “Global Britain” campaign.

After making only 11 foreign trips since July 2019, nine of them to Europe, a key sign that change is on the horizon for Johnson is his trip to India next month. It will be his first to the country (and indeed the massive Asia-Pacific region) as prime minister. He will be guest of honor at the annual Republic Day parade in New Delhi, and he intends to send a signal of what is to follow during the rest of 2021 and beyond.

For the UK Government, Global Britain is all about reinvesting in relationships, championing a rules-based international order, and demonstrating that England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are open, outward-looking and confident on the world stage. So it is no coincidence that India was selected as the prime minister’s first overseas port of call in 2021.

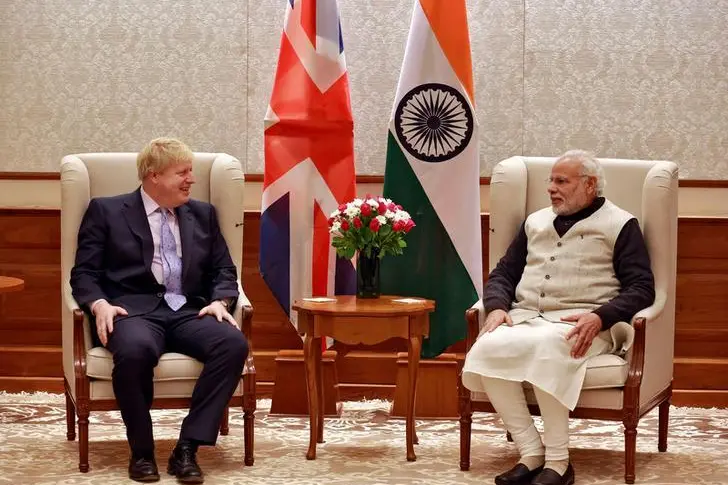

London and New Delhi have, of course, long had a unique relationship, dating back to the days of the British Empire. But the growing warmth in bilateral ties under the leadership of Johnson and his Indian counterpart, Narendra Modi, is striking — including, during the coronavirus crisis, a flow of medical goods from India to the UK. The letter has, for instance, received 11 million face masks and 3 million packets of paracetamol from the former since the pandemic began.

Both Johnson and Modi attach high importance to bilateral relations, and in 2018 Modi became the first Indian premier to visit Britain in more than a decade.

Under Johnson, the UK has at least three significant reasons for wanting to enhance the relationship with India as much as possible. Firstly, the cooling of ties with China has been more pronounced in London than in many other European capitals. In this context, the second reason is that London would like New Delhi to play an ever-increasing role in international affairs. To this end, Johnson has invited India — along with fellow G20 states South Korea and Australia — to next year’s UK-hosted G7 summit, as part of his ambition to work with a group of like-minded democracies to advance shared interests and tackle common challenges.

The third reason is Brexit. After leaving the EU, Johnson wants to agree a new UK-India trade deal that will grant UK firms greater access to a market that includes about 1.3 billion consumers.

The strength of the contemporary economic relationship between the two countries is underlined by the fact that the UK is one of the biggest G20 employers and investors in India. More than 400 British firms have a presence there.

India, meanwhile, is one of largest sources of foreign investment in the UK, with more 800 Indian companies operating there.

There are several distinctive elements of this economic relationship — which has come to dominate bilateral ties recently — that Johnson wishes to emphasize in a post-Brexit trade deal. Firstly, he wants even stronger cooperation in defense manufacturing, as part of a wider bilateral dialogue on security and defense. Secondly, he wishes to encourage further international investment, via the City of London, in Indian infrastructure.

The third element he wishes to emphasize is technology, given the significant investment in Indian telecoms and tech by UK-headquartered firms. A fourth is the health, pharmaceutical and life sciences sector. As the “pharmacy of the world,” India supplies more than 50 percent of the world’s vaccines. More than a billion doses of the UK-developed Oxford University/AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine will be manufactured at the Serum Institute in Pune, for example.

Yet, despite all the potential gains from a trade deal, there are some challenges that Johnson must face, too. One key issue India is pressing for in a wider agreement is UK immigration reforms that would allow more Indian businesspeople and students to travel to England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

However, despite the differences that remain between India and the UK on the details of a post-Brexit trade deal, what is striking is how much economics has come to dominate bilateral relations in recent times.

As this has happened, some traditional irritants have been de-emphasized, including concerns about human rights issues in India. In 2013, for example, a motion was tabled in the House of Commons calling on the UK government to reinstate a previously imposed travel ban on Modi, citing “his (alleged) role in the communal violence in 2002” in Gujarat.

As Johnson continues to prioritize greater post-Brexit ties with India, controversies such as this have been set aside. During his time in power, any irritants in UK-India relations look likely to be overridden by a desire for greater economic cooperation, as London seeks to balance its cooling relations with Beijing by developing warmer ties with New Delhi.

- Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics

Copyright: Arab News © 2020 All rights reserved. Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (Syndigate.info).