PHOTO

HONG KONG - After crushing student protests in 1989, the Chinese Communist Party promised citizens prosperity in exchange for compliance. Wages have risen 40 times since then, but inequality has soared too. Controls have tightened. Now President Xi Jinping is again asking youth to bear the brunt of the economic burden, from bad debts to the trade war.

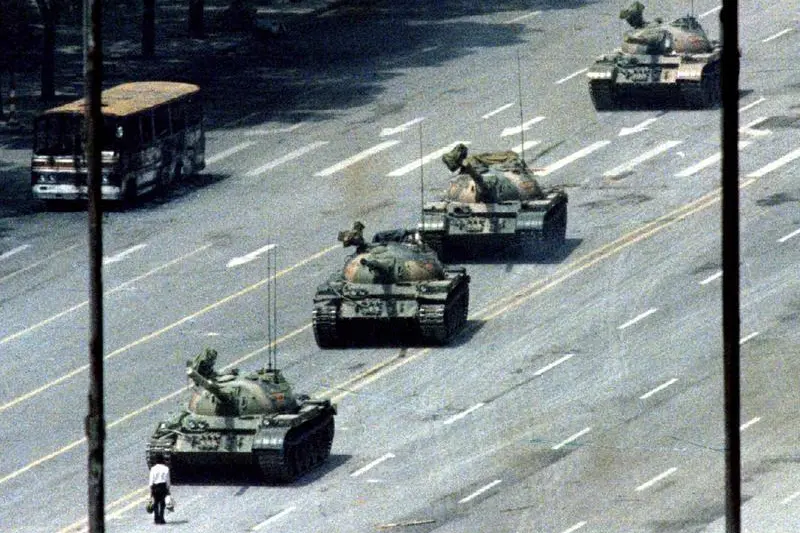

Thirty years ago, on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, Chinese soldiers fired on unarmed civilians to end weeks of protests in front of the Forbidden City. The demonstrators had various agendas, which made negotiations challenging. Underlying them all was economic anxiety: relaxed price controls generated 28% consumer inflation in February 1989, a record never surpassed. But the worst came later, when tanks withdrew and international sanctions set in. Between 1988 and 1990, growth slowed from 11.2% to 3.9%.

What happened next is key: China opened up to trade and investment, allowed market reforms, and eased up politically. The ensuing accrual of wealth built up a $13 trillion economy and convinced many citizens that whatever had happened at Tiananmen had probably staved off instability that might have slowed their escape from poverty.

But the social compact in which obedience secured better living standards is fraying as growth slows. Beijing is once again tightening control on young workers: in 2018, police began detaining Marxist college students for supporting union organisation at Jasic Technology in Shenzhen.

For a widening swathe of young blue- and white-collar workers in China – just like the crowd that clogged Tiananmen Square three decades ago – there is a worrying despondency that supports entire product lines with tongue-in-cheek brand names like "Achieved-Absolutely-Nothing Black Tea". With that comes the financial malaise and disaffection that have plagued developed economies, and sparked movements like France’s gilets jaunes. Data supports the disgruntled masses: the World Inequality Database shows the top 1% of China's population now holds 30% of national wealth, twice what they had in 1995, while the bottom half’s share has fallen to just over 6%.

Unfortunately China can’t afford the cynicism of developed economies. It needs its 20-somethings to produce, consume and pay lots of taxes. It has a GDP per capita around $9,000, lower than Russia – but has the demographic profile of a far richer country. Official estimates have the national pension fund running deficits by 2028, and insolvent by 2035 - yet there will be only a single worker for every pensioner by 2050, when one-third of the population will be over 60. China also needs to outgrow or pay back at least 2 trillion yuan ($290 billion) in bad bank debt.

This would be manageable if the private sector were generating high-paying jobs. But that boom is stalling. Both manufacturing and non-manufacturing indexes have been in contraction since late 2018, and survey data shows the services sector has not picked up the slack, as in the past.

The university system still struggles to prepare graduates for the workforce - something that bothered the Tiananmen protesters too. New hires thus endure low wages and long hours. Alibaba BABA.N founder Jack Ma, for example, promotes a “9-9-6” schedule - 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., 6 days a week. Misguided labour protection laws have translated into a shift toward contract work and underemployment. A tech boom that once created jobs has wound down too; now overextended internet stars like JD.com and Tencent are slashing headcount. Data from Gavekal Dragonomics shows investment in startups - another key font of new jobs for graduates - began plunging in 2018 and has not recovered.

The economic consequences could be severe, ranging from consumption to entrepreneurship. High house prices are squeezing disposable incomes, eating away at young shoppers’ ability to buy cosmetics, plane tickets and the like. Household credit has exploded, largely thanks to the younger generations, the first to tap the explosion in credit card issuance and consumer loans. Indebted millennials may find it even harder to shoulder Xi’s load.

The new generation can live in a cooler economy. But getting by was not the "China Dream" of wealth and rejuvenation sold by Xi. Nor will stoicism alone turn the economy around the corner. This generation’s China dream may end with a whimper, not gunshots, but the consequences would be no less dire.

On Twitter https://twitter.com/petesweeneypro

CONTEXT NEWS

- The Tiananmen Square protests were part of a student-led movement in Beijing and other Chinese cities in mid-1989. On June 4, troops with assault rifles and tanks fired at demonstrators trying to block their advance towards the square. Estimates of the death toll vary from hundreds to thousands.

- For previous columns by the author, Reuters customers can click on SWEENEY/

- SIGN UP FOR BREAKINGVIEWS EMAIL ALERTS: http://bit.ly/BVsubscribe

(The author is a Reuters Breakingviews columnist. The opinions expressed are his own)

(Editing by Clara Ferreira Marques and Katrina Hamlin) ((pete.sweeney@thomsonreuters.com; Reuters Messaging: pete.sweeney.thomsonreuters.com@reuters.net))