By NJ Ayuk, Executive Chairman, African Energy Chamber (https://EnergyChamber.org).

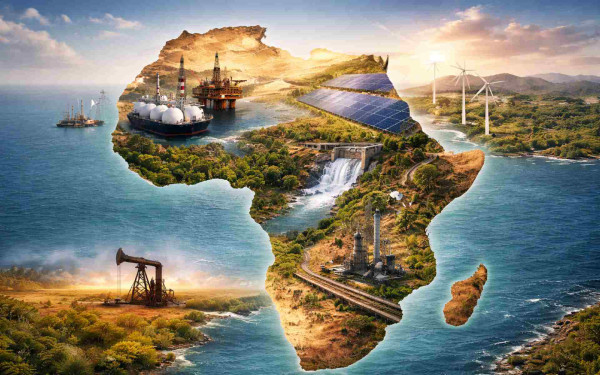

Let’s really think about this: Today, Africa contributes less than 5% of the world’s energy-related emissions, despite being home to 19% of Earth’s population. By 2060, the continent’s population is expected to reach 28% of the global total. But guess what? In that same timeframe, its share of energy-related emissions is projected to remain a modest 9%.

When you consider these statistics compiled in the recently released African Energy Chamber’s “State of African Energy: 2026 Outlook Report,” it’s evident that Africa’s responsibility for climate change is minimal at most. And yet, the Western advocates who continue the chant of “NET-ZERO! NET-ZERO!” expect their calls for rapidly phasing out fossil fuels to be enacted universally.

This makes ZERO sense.

Low per-capita energy use actually positions Africa to drive global decarbonization efforts. However, this low-carbon development pathway must be one that respects the unique needs of Africans.

It’s just a fact that infrastructure limitations make large-scale decarbonization more challenging on the continent than in other parts of the world. A lack of grid capacity, outdated transmission lines, and a significant energy deficit hinders the integration of large-scale renewable energy projects, such as solar and wind farms. A significant portion of the population lacks access to reliable electricity, and the continent as a whole faces energy deficits, which means decarbonization efforts must occur alongside the fundamental need to expand energy access.

Addressing such infrastructure challenges requires more than just building new assets — it also requires modernizing grids, promoting energy efficiency, improving regulatory environments, and fostering local expertise. Amid emissions regulations drafted by both the International Maritime Organization and the European Union, Africa has the potential to serve as a major green fuel supplier. But this potential cannot be reached without significant investments in infrastructure upgrades.

As we are all too aware, transitioning to a low-carbon economy requires significant upfront investment. Many African countries struggle to secure the necessary capital due to perceived political and financial risks. Inconsistent policies and slow permitting processes create uncertainty for investors, despite many governments setting ambitious decarbonization targets. A heavy reliance on fossil fuel exports means that many African nations will need to walk a fine line between economic stability and the transition to clean energy.

Despite its dependency on fossil fuels, Africa’s evolving energy profile — that includes hydrogen and critical minerals — has the potential to play an essential role in shaping global climate outcomes.

Growing Green Hydrogen

The 2026 Outlook reports that, by 2035, the continent could produce over 9 million tonnes of low-carbon hydrogen annually. Achieving this volume could be key to the nation’s decarbonization efforts. This is thanks to Africa’s vast solar and wind resources, extensive land availability, and proximity to major export markets. In fact, our report sees the continent becoming an exporter of hydrogen, either by transporting it as liquid via pipeline from Northern Africa to Europe or by using ammonia as a carrier to other international markets.

Currently, major green hydrogen projects in Africa are concentrated in Namibia, South Africa, Mauritania, Egypt, and Morocco. In 2022, these four nations joined two others — Egypt and Kenya — in launching the African Green Hydrogen Alliance (AGHA) that promotes Africa’s leadership in green hydrogen development. Now up to 11 members, the AGHA anticipates that green hydrogen exports from the continent will hit 40 megatons by 2050.

Namibia is a leader in the development of green hydrogen, particularly for export. The USD10billion Hyphen green hydrogen project, being developed by Namibian company Hyphen Hydrogen Energy — a joint venture between German energy company Enertrag and Nicholas Holdings — expects to produce more than 300,000 tons of green hydrogen annually, aimed at export to Europe.

Another Namibian-German partnership is the HyIron Oshivela green ironworks, which uses a 12 MW electrolyzer, powered by a roughly 25 MW solar array and large battery system, to generate green hydrogen. The hydrogen is then used to remove the oxygen from iron ore to create direct-reduced iron (DRI), a key feedstock for low-carbon steelmaking.

Meanwhile, construction is underway on the Daures Green Hydrogen Village, Africa's first fully integrated green hydrogen and fertilizer production facility, which will combine renewable energy with sustainable agriculture.

Neighboring South Africa has established a national "Hydrogen Valley," home to several large-scale projects that are successful largely thanks to public and private investment. The Coega Green Ammonia Project is a USD5.7 billion plant by Hive Hydrogen and Linde, projected to produce up to 1.2 million tons of green ammonia per year. The Prieska Power Reserve Project, located in the Northern Cape, is expected to begin producing green hydrogen and ammonia from solar and wind energy starting in the coming year. In August 2023, Sasol started operations at Sasolburg Green Hydrogen Pilot. This pilot program is capable of producing up to 5 tons of green hydrogen per day. And a consortium known as the HySHiFT Project is looking to produce sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) using green hydrogen in existing facilities.

In the north, Mauritania is pursuing large-scale "megaprojects" to capitalize on its extensive wind and solar potential. Project Nour (Aman) is one of Africa's largest green hydrogen projects. Developer CWP Global hopes to produce 1.7 million tonnes of green hydrogen annually. The Mauritanian government has also entered into a separate $34 billion agreement with Conjuncta to develop a 10GW green hydrogen facility.

Further north, Morocco stands out as one of the first African nations to develop a national green hydrogen strategy. It is now positioning itself for export to Europe by allocating substantial land near ports and investing in shared infrastructure to facilitate production and export. Projects are underway in collaboration with entities like TotalEnergies and the European Investment Bank.

Egypt is also actively working to become a regional hub for hydrogen and its derivatives, with a strong focus on the Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCEZ). The SCEZ is already having an impact: The Ain Sokhna Plant, located within the zone, is the first operational green hydrogen production plant in Africa. The Egyptian government has also signed numerous international agreements and secured over USD17.4 billion in investment commitments for several major green hydrogen projects.

Critical Diversification

In addition to its vast green hydrogen potential, Africa is also home to some of the world’s richest deposits of critical minerals such as cobalt, copper, gold, lithium, and platinum group metals (PGMs). As the 2026 Outlook forecasts, this bounty positions the continent as a pivotal player in the global supply chain during energy transition.

We expect demand for critical minerals to quintuple by 2035. This means that mineral-rich African nations stand to gain a significant strategic foothold in the industry, with opportunities all along the value chain from extraction to processing to refining — as long as they can pull in sustained investment in infrastructure, governance, and skills development.

Continued investment is the essential ingredient for the success of this sector. And the good news we’re reporting is that governments in other regions (particularly the United States and China) are clamoring to secure bilateral agreements with African countries to secure mineral access, promote joint ventures, and integrate mineral value chains.

Over the past year, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has led the world in cobalt production and ranked second in copper production. As we reported, the DRC was home to seven of the top 10 cobalt-producing mines in 2024. But in February 2025, the government imposed an export ban to curb oversupply and stabilize falling prices. While the ban was lifted in October, it was replaced with a strict quota system to govern mined output and exports until 2027 at the earliest.

The DRC also joins Zimbabwe, Mali, Ghana, and Namibia in leading lithium production. This group of nations produced 124,230 metric tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) in 2024, and output is expected to grow over 150% by 2030. As the 2026 Outlook notes, Africa’s lithium mines are cost-competitive — making them an ideal investment target. So far, several projects have been developed quickly and at relatively low capital costs, particularly in Mali and Zimbabwe.

As for Zimbabwe, its strategic importance in the lithium supply chain continues to grow: In 2024, it was home to two of the world’s top 10 lithium-producing mines, collectively accounting for 7.42% of global lithium output. Zimbabwe also leads beneficiation efforts, having banned lithium ore exports and introduced a 2% royalty on lithium sales, while advancing a USD450 million refinery at the Mapinga industrial park.

Unlocking Our Mineral Potential

Based on our research, the 2026 Outlook outlines several strategies that we believe will help unlock Africa’s downstream potential in a rapidly evolving global minerals landscape.

For one, stable and transparent regulatory frameworks are a must. Securing long-term, consistent investment in refining and processing infrastructure requires predictable legal and fiscal environments. Governments must make regulatory clarity a priority, streamlining permitting processes and ensuring consistent enforcement to attract both domestic and foreign capital.

Promoting regional cooperation and sharing clean-energy infrastructure is another strategy. Governments and regional blocs should focus on investment in shared industrial infrastructure, such as roads, rail, and renewable energy corridors, to support clusters of processing facilities. Regional cooperation — standardizing export policies, environmental standards, and investment incentives across borders — is essential to overcome the fragmented nature of African markets and the landlocked geography of many resource-rich countries.

We also need to ramp up our efforts to build local technical capacity and enable technology transfer. Africa’s refining ambitions are hampered by the scarcity of skilled labor and the limited access to advanced processing technologies. Governments should provide incentives for local hiring, training, and R&D, encouraging partnerships with universities, technical institutes, and international development agencies to accelerate workforce development and knowledge transfer.

At the same time, we must avoid the human rights violations that have plagued other extractive industries in Africa. Our regulations must prioritize human dignity and workplace safety, with directives in place that criminalize child labor, safeguard indigenous people, protect the local physical environment, and promote healthy living and working conditions.

African leaders need to embrace this moment as an opportunity to move up the value chain into processing and refining. The continent can and will unlock significant economic value to help raise nations out of energy poverty – only if governments can foster sustained investment in infrastructure, governance, and skills development.

"The State of African Energy: 2026 Outlook Report" is available for download. Visit https://apo-opa.co/4qWPhGB to request your copy.

Distributed by APO Group on behalf of African Energy Chamber.