PHOTO

By Carolyn Crist

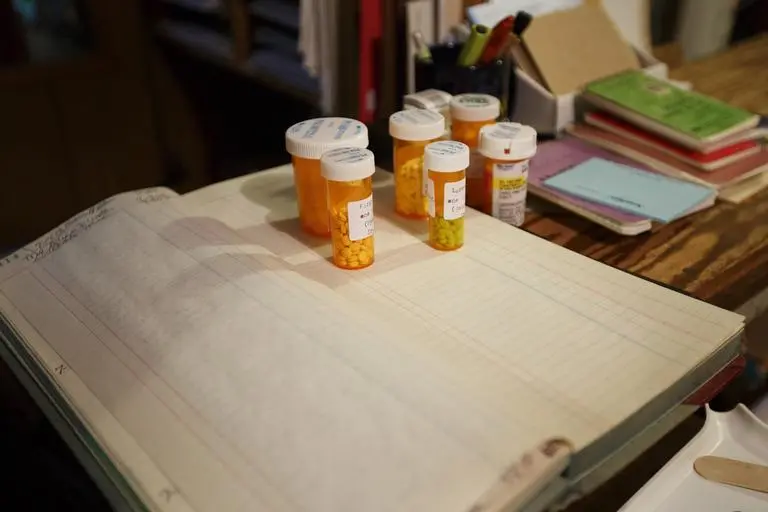

(Reuters Health) – Opioid pain relievers such as codeine and hydrocodone often aren’t stored safely in households with children, according to a new study.

About one in three parents with children under age 7 reported storing their opioid prescription by locking it up, and about one in 11 parents with children between ages 7 and 17 remembered storing their medicines properly.

“Parents know their children best and often think having medicine under lock and key isn’t necessary, especially as kids get older, but we’ve seen hospitalizations double since the 1990s,” said lead study author Eileen McDonald of the Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy in Baltimore, Maryland.

“We want to think the best about our kids, especially when it comes to alcohol and drug avoidance, but most start using from family and friends,” she told Reuters Health. “Given the pervasiveness of opioids at home, parents need to have safe storage or remove them completely when not being used.”

McDonald and colleagues surveyed 681 adults who used opioid pain relievers in the past year and had children under age 18 at home. For those with young children under age 7, about 33 percent said they locked up their medicine, and 12 percent of those with older children put their medicines in a locked area. In families with both age groups, about 29 percent of parents used lockable storage.

The research team also asked about parents’ beliefs and actions regarding opioids in the home. Parents with younger children were more likely to worry about their kids and say that children can overdose on opioids. Parents with older children were half as likely to report safe storage as barriers increased, saying that storing medicine in a locked place takes too much time or makes it too hard to take the medicine.

“We were most surprised to see that more than half of the parents had heard about a child who died from getting into their parents’ opioids at home, but that didn’t change their behavior,” McDonald said.

Opioid use in the United States has soared in recent years. Almost 2 million Americans start new opioid pain relief prescriptions annually, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Overall, more than 250 million opioid prescriptions are filled each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In many cases, the drugs are prescribed to help with pain after surgery.

High opioid use has been linked to abuse, heroin use and higher numbers of drug poisoning deaths, especially in children, the study authors wrote in Pediatrics. In fact, opioid-related hospitalizations for children have doubled from 1997 to 2012, according to a December 2016 study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“The largest increase occurred in children ages 1 to 4, which is scary,” said Julie Gaither of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Gaither, who was not involved with this study, was lead author of the 2016 JAMA Pediatrics report.

“Children are our most vulnerable group, and it’s important to speak to parents and find out what they really know about opioids,” she told Reuters Health. “My sense is that they don’t really know what an opioid is or how to store it safely.”

Along with codeine and hydrocodone, opioids include oxycodone, methadone, hydromorphone, morphine and fentanyl.

When these drugs aren’t in use, poison control groups recommended safely disposing of them. Instead of flushing them down the sink or toilet, which can harm the water system, mix the medicines with unpalatable substances, such as coffee grounds or cat litter, and throw them away. Alternatively, search online for an officially approved disposal site, such as a local drugstore or police station.

“The opioid problem is complex, but for kids, it doesn’t have to be,” Gaither said. “The solution is simple - keep the drugs away from kids by keeping them out of the house.”

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/2lBF1Wv Pediatrics, online February 23, 2017.

© Reuters News 2017