PHOTO

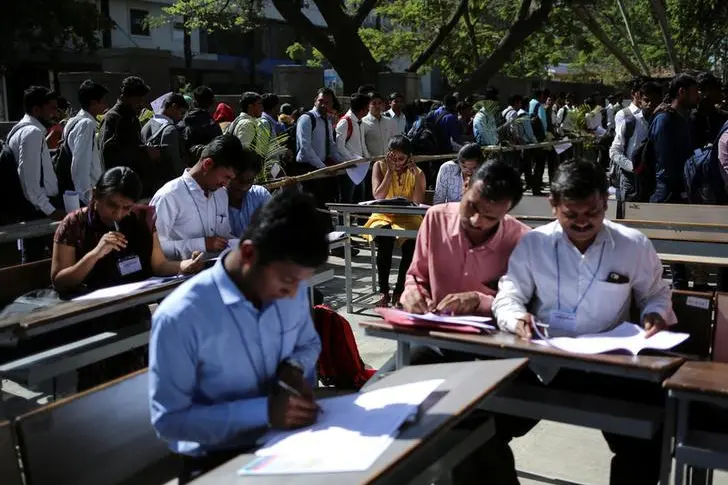

MUMBAI - Robots are coming. Headless skeletal frames will soon take over. Clever, more reliable, versions of ourselves with endless productive capacity will replace human labour. Jobs will be lost and the way people live and work will forever change, and perhaps not for the better. This disconcerting vision is the prevailing view of how automation, artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things will transform the world of work. As industrial robots help rich countries bring production back onshore, underemployed countries like India, with a population of 1.3 billion and 90 million people reaching working-age over the next decade, have the most to lose.

There could be an alternative way forward: technology advances can help poor countries create more employment. That’s the vision Natarajan Chandrasekaran, head of India’s giant Tata conglomerate, and Roopa Purushothaman, the group’s chief economist, lay out in “Bridgital Nation”. Despite its clunky title, the book tackles the central issue that will define Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s next five years in power.

Tata has form when it comes to reimagining work. The group’s $110 billion subsidiary, Tata Consultancy Services, shook up the way people and technology operate during the outsourcing boom that prompted large Western companies to relocate back offices, call centres and software development to the South Asian nation. Chandra, as he’s widely known, led the company during some of its heyday before taking charge of the wider group.

The authors offer a refreshing perspective on the human problem which is otherwise mostly viewed through a developed-market lens. Artificial intelligence, they argue, can help India address a massive shortage of doctors, teachers, judges, and childcare workers by creating a new class of workers able to use technology to ease administrative burdens. That should free up senior professionals to focus on the job in hand. It’s a version of the collaborative robots, or “co-bots” that help human workers to make common-sense decisions in automated factories.

Take healthcare. India currently only has 700,000 practicing doctors. Though that number will rise to about 1 million by 2030, it will still be well short of the 1.5 million needed to meet World Health Organization standards. A transformation of the public health system, automating some tasks, and reassigning others to a new class of digitally enhanced healthcare workers, could free up enough hours to create the equivalent of 370,000 doctors. Contrary to the prevailing gloomy narrative about the effects of automation, Chandra and Purushothaman argue that gains in productivity will actually boost wages.

An innovative fix is certainly needed. The book is crammed with heart-rending stories and statistics about the sorry state of India’s workforce: 18% of young people between the ages of 15 and 29 are unemployed, just 23% of working-age women actually work and participation rates are falling. Meanwhile 77% of India’s employed are stuck in the informal sector, one largely defined by low productivity and lack of social security.

“Bridgital Nation” provides some hope of filling in the missing middle in a country split between a high-skilled, intensely productive, organised sector at one end and an informal sector with many more people at the other. The potential rewards are startling: India could, for example, add about $480 billion to its GDP simply by bringing into active employment half of the 120 million women with at least a secondary education who are not working. Other developing countries could follow a similar path.

The authors’ proposed solutions are not out of India's reach. The recent creation of a giant biometric identity scheme covering one billion Indians, linking everything from their tax returns to their mobile phones and bank accounts, is a huge step forward. The government-backed online payments infrastructure is arguably the best in the world, allowing everyone from Alphabet-owned Google to Walmart's PhonePe to drive a digital revolution that will ultimately improve tax compliance. These are both brilliant examples of what India can achieve by deploying technology in a focused way.

There’s little discussion, though, of who will create these new systems or fund the overhaul. The writers avoid any mention of how technology could kill off India’s already underwhelming manufacturing sector. There is also an almost utopian notion that countries can choose the speed at which they adopt and deploy technology. True, India’s low-cost labour means it might be less vulnerable than other countries. But ultimately companies, including private firms in the healthcare industry, will not hesitate to deploy robots in a way that gobbles up more jobs than it creates, unless they are shown another way. That best hope is that the government will lead. That requires a very human leap of faith.

CONTEXT NEWS

- “Bridgital Nation: Solving Technology’s People Problem", by Natarajan Chandrasekaran and Roopa Purushothaman, was published by Penguin on Oct. 12.

- Chandrasekaran is the chairman of Tata Sons, the holding company of one of India’s biggest business groups. Purushothaman is the chief economist for the wider Tata group.

(Editing by Peter Thal Larsen and Katrina Hamlin) ((una.galani@thomsonreuters.com; Reuters Messaging: una.galani.thomsonreuters.com@reuters.net))