PHOTO

As the 2023 parliamentary elections begin to loom over Turkish politics, the country’s Kurdish electorate is starting to move. Some Kurdish politicians have proposed distancing themselves from the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which is designated as a terrorist organization by many NATO and EU countries.

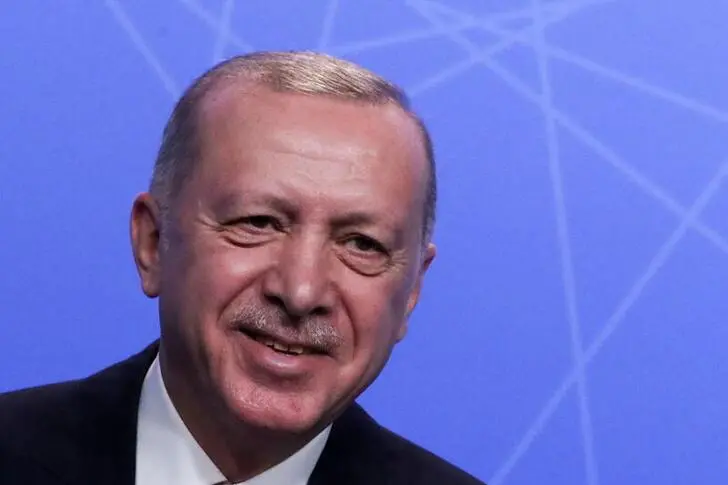

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is very much aware of this dichotomy. Latest public opinion polls show that the support for his unofficial coalition partner, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), may not be sufficient to help him form a government.

Erdogan’s approach to the Kurdish issue has an interesting background. In 2009, he launched an initiative to bring a lasting solution to Turkey’s Kurdish problem. It was referred to as the “Kurdish Opening.” Hopes were very high because a strong leader like Erdogan could easily sell any solution to the electorate. A negotiation process was initiated with Abdullah Ocalan, the jailed leader of the PKK terrorist organization. After several ups and downs and ensuing intervals, a set of comprehensive talks were held to finalize the deal. The outcome was transformed into a law with a long title: “Law on putting an end to terror and strengthening social integration.” This was enacted in July 2014. For the first time in decades, an opportunity looked to be in the pipeline to solve Turkey’s perennial Kurdish problem.

In the June 2015 elections, Erdogan lost by a small margin. His Justice and Development Party (AKP) claimed 40.87 percent of the vote, which corresponded to 49.83 percent of the seats in parliament. The AKP thus lost an election for the first time, while a pro-Kurdish party — the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) — became the third-biggest in the legislature. However, the opposition parties could not capitalize on this golden opportunity and failed to form a coalition government that would have ousted Erdogan’s AKP.

Erdogan abruptly interrupted the Kurdish Opening process. He claimed that it was conducted without his consent. A wave of violence then broke out in the Kurdish-inhabited regions of Turkey. Media reports claimed that the security forces were instructed to keep away from the clashes so that the damage would be greater.

New elections were held in November 2015 and, this time, Erdogan’s AKP won a comfortable majority. The party increased its vote share to 49.5 percent and its number of seats from 258 to 317. This paved the way for Erdogan’s ascendance to the presidential system with extensive powers.

Now, in the run-up to the 2023 elections, public opinion polls do not promise an encouraging result for Erdogan. His Achilles’ heel is the falling support for the ally of the ruling party, the MHP. As this coalition partner threatens to fall short of helping the AKP form a government, the Kurds may emerge as kingmaker in this and perhaps many future elections — as long as Erdogan does not succeed in fragmenting them. The Kurds constitute a block of 11 to 13 percent of Turkey’s voters. The MHP’s acquiescence to be part of a government together with the Kurds is the last thing that one can think of.

Erdogan has treated the Kurdish electorate so badly that, even if the main pro-Kurdish party — the HDP — agrees to cooperate with him, the grassroots may refuse to vote for it. This is partly because Erdogan dismissed several elected mayors in Kurdish-inhabited provinces and replaced them with appointed mayors. This was in stark contrast to his initial philosophy, because, in the early years of the AKP government, he had insistently defended the primacy of elected administrators over appointed ones.

Meanwhile, there is a court case in progress in Turkey’s Constitutional Court to dissolve the HDP. Selahattin Demirtas, the former co-chair of the party, is still being kept in jail despite a 2018 verdict by the European Court of Human Rights calling on Ankara to immediately release him. Another Kurdish member of parliament, Omer Faruk Gergerlioglu, has served a jail term for retweeting a story on Twitter.

Against this background, Erdogan last week paid a visit to the eastern city of Diyarbakir, which is considered to be the ideological capital of the Kurds. He has avoided such a visit for more than two and a half years. In the past, he used to visit the area almost every six months. Political analysts wondered whether this visit, after such a long interval, would herald some sort of reconciliation with the Kurdish voters or whether it was a sign of preparations for early elections.

In Diyarbakir, Erdogan refrained from committing himself to reconciliation with the pro-Kurdish HDP. Instead, he accused it of being responsible for the collapse of the Kurdish Opening.

The die is not yet cast. We will have to wait and see what surprise Erdogan pulls from his sleeve next.

- Yasar Yakis is a former foreign minister of Turkey and founding member of the ruling AK Party. Twitter: @yakis_yasar

Copyright: Arab News © 2021 All rights reserved. Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (Syndigate.info).