PHOTO

Since October 2019, Lebanon has faced one of the worst economic crises in the world, against a backdrop of political gridlock and an economic and political system that is fast running out of steam. The COVID-19 pandemic and the explosion which ravaged the capital, Beirut, in August 2020 have both played their part in the deterioration of peoples morale, as well as their physical wellbeing. These crises pile up and compound each other.

Many NGOs, including Mdecins Sans Frontires/Doctors Without Borders (MSF), already work in Lebanon, which has experienced several tragic episodes over the past few decades. This crisis is far from being the countrys first, and among our colleagues and other Lebanese health professionals, the feeling is that the worst is yet to come.

Every day we see things in MSFs projects that alarm us. Patients with chronic illnesses now do not only ask for medication, but also for food. More and more Lebanese people are seeking care in clinics initially designed for Syrian and Palestinian refugees, and there are perpetual queues outside for our mother and child health care clinic. The palpable effects on our activities reflect an overall situation whose deterioration is accelerating, where only the most well-off are spared.

The countrys slide toward ruin is dizzying. The Lebanese pound has already lost 90 percent of its value and the price of bread has more than doubled in a year. Medical equipment and materials, as well as certain drugs, are no longer being imported, or are hoarded by importers to be sold at inflated prices later on. Little by little, the Lebanese health care system is breaking. According to the World Food Program, in May this year, 23 percent of Lebanese people and half of all Syrian refugees in Lebanon experienced food insecurity. The Central Bank, depleted of funds, could withdraw food subsidies at any time, which risks further aggravating the situation. Despite the much-vaunted Lebanese resilience, and the solidarity shown by its diaspora community, the situation has become untenable.

The increase in prices, as well as the frequent power cuts and fuel shortages, have put the very functioning of hospitals at risk. Those Lebanese that are lucky, educated or connected enough are leaving the country out of despair. Among them are many doctors and nurses. In May 2021, 1,300 doctors left the country, according to the Lebanese doctors association. This further reduces peoples chances of accessing health care.

MSF is trying to adapt to these new needs. During the COVID-19 crisis MSF worked hard to maintain our essential services (maternity, treatment for chronic illnesses, etc.), while establishing dedicated care for patients with COVID-19 in one of its hospitals. For us, this was also a time to better understand the extent to which the Lebanese public health system can play its role. Despite the severity of the pandemic, the large number of patients needing hospitalization and their minority presence in the country, the public hospitals were first to respond. It is essential that their role be reflected in greater funding and support. In contrast, private hospitals joined the response only when forced to and later than they should have considering they represent 80 percent of health facilities in the country.

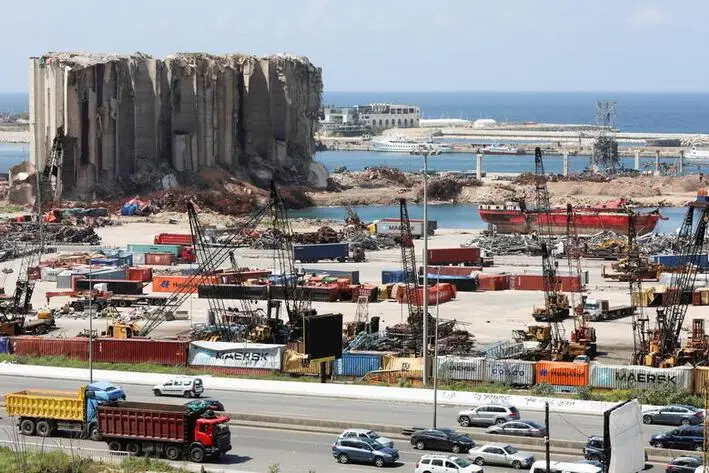

The double explosion at Beirut Port on Aug. 4, 2020, led to a national and international outpouring of solidarity. But the scale of the crisis that is unfolding today is beyond measure, and it is leading the country down an unprecedented path. In conditions like these, local and international humanitarian organizations like MSF cannot prevent the worst from happening. The best that we can do is the equivalent, I fear, of putting a band-aid on an open wound.

But its not too late to avoid the worst. Public hospitals still exist, part of the Lebanese medical corps is still here, and the network of health centers is holding, even if weakly, for now. What remains of health services must be protected, and the means to keep medical personnel in Lebanon must be found rather than waiting until the country needs external and direct humanitarian aid on an even greater scale.

International economic aid that is ready to be deployed to Lebanon exists (through the IMF, or CEDRE, for example). However, this is conditional on structural reforms being made and therefore on the formation of a government. Yet this has been blocked for nearly two years. What will happen if, as is likely, the paralysis endures?

The Lebanese people, migrant workers and refugees in Lebanon cannot continue to be held hostage to the gridlock and infinite political negotiations. Alternative solutions that ensure access to essential services for the most vulnerable people must be found immediately. Access to medicines and treatment, as well as access to water and food, must be protected, even made sacred.

Julien Raickman is MSF head of mission in Lebanon. He has previously worked in Afghanistan, Libya, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt and Syria for MSF and other NGOs.

Copyright 2021, The Daily Star. All rights reserved. Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (Syndigate.info).