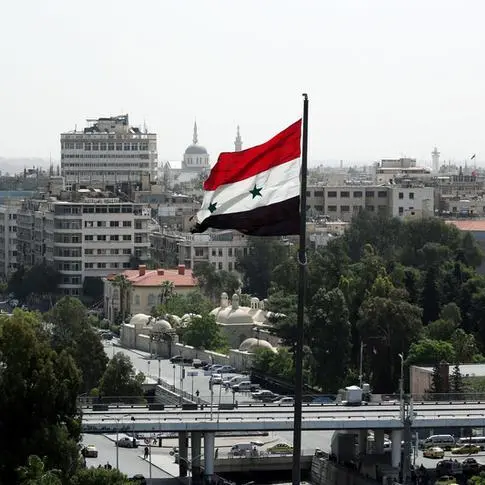

PHOTO

TADEF, Syria- Using trench and tunnel warfare, Syrian rebel fighter Abu Ahmad said he and his group held out for years against government forces in eastern Ghouta until Russian air power came to President Bashar al-Assad's aid in 2015, to devastating effect.

As he follows the news from Ukraine, Abu Ahmad is reminded of the pivotal role Moscow played in turning the tide of the conflict in favour of Assad and against rebels seeking to topple him, using siege warfare and ferocious bombardment.

"Nobody stopped Russia - neither the West nor the Arabs - from fighting Syrians, so they headed to Ukraine for the bigger war," said Abu Ahmad, speaking from Tadef, a town in northern Syria where he mans a position on the frontline separating him from Russian-backed government forces.

Eastern Ghouta, on the outskirts of Damascus, suffered the longest running siege in modern history - more than five years - before succumbing in 2018 to a Russian-backed offensive.

U.N. investigators found the siege and recapture of eastern Ghouta were marked by war crimes and crimes against humanity. The campaign to take back the area included indiscriminate attacks that hit homes, markets and hospitals, they added.

For Syrians who lost family, friends and their homes in Russian-backed offensives, headlines from Ukraine are stirring memories of a conflict that destroyed much of their country in the last decade.

As the conflict in Syria marks its 11th anniversary next week, the echoes grow louder.

Russian forces are besieging Ukrainian cities, civilians are caught in shelling and calls for the imposition of a no-fly zone have gone unanswered. Evacuation corridors have been opened in some cities to allow residents to flee, although both sides have accused each other of breaking ceasefires.

Hundreds of thousands of people were killed in Syria's war, which spiralled from an uprising against Assad's rule in 2011 and forced more than half of Syrians from their homes - millions of them abroad as refugees.

After Russia's deployment to Syria in 2015, rebel enclaves that withstood years of siege and attack - including the use of chemical weapons - fell one by one. Syria has denied using chemical weapons.

Abu Ahmad recalls how a Russian strike in eastern Ghouta killed 17 fellow fighters as they sheltered in a tunnel that had previously been safe from government assaults.

He left eastern Ghouta, along with tens of thousands of other Syrians, when it fell to government forces, leaving through a safe corridor to the rebel-held north instead of risking life back under Assad's rule.

FROM ALEPPO TO UKRAINE

Syria's main frontlines have been frozen for several years, and the country is split into separate zones where Russia, Turkey and the United States hold sway.

Washington and other foreign adversaries of Assad once supported some of the rebels, but never with enough firepower to topple him.

Tadef, located within Turkey's zone of influence, has changed hands several times, and was once under Islamic State control. Homes are riddled with bullet holes, and the streets are largely deserted.

Demolished buildings bear witness to Russian air power.

Syrians from all over the country who fled Assad's rule live here today, including people displaced from Aleppo when its rebel-held districts fell to the government in 2016 after a months-long siege, enforced with Russian help.

"They (pro-government forces) started hitting us more and more, instead of one jet, there were 5, 6, 10 or 15 hitting us," said Mahmoud Madarati, 55, who has lived in Tadef since fleeing Aleppo, recalling the impact of Russia's entry to the war.

Other parties in the Syrian conflict have also been accused of causing civilian casualties, including the U.S.-led coalition that has battled Islamic State.

However, the extent of death and destruction caused by Russian bombardments has been far greater, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, which reports on the war using a network of sources across Syria.

Moscow says it intervened in Syria at the government's request to help fight terrorists.

It denied targeting civilians in Syria, just as it denies doing so in Ukraine.

Ukraine and its allies call Russia's actions a brutal invasion that has killed hundreds of civilians. Apartment blocks have been reduced to rubble, towns have been evacuated and 2 million Ukrainians have fled the country. Kyiv has accused Moscow of war crimes.

Putin says Russia launched a special operation to destroy its neighbour's military capabilities and remove what it regards as dangerous nationalists in Kyiv.

'UKRAINIANS BEWARE'

Though Tadef is mostly calm these days, Madarati's seven-year-old son was wounded by shelling from government-held areas seven months ago. His leg and hand were amputated.

"They (the Russians) finished with Aleppo, and now they have moved to another country, and who knows where they will go next," Madarati said.

Like others, Madarati left Aleppo through a corridor set up under Russian supervision as pro-government forces were pressing the attack. Such corridors were a feature of the war as Assad's opponents streamed out of defeated enclaves all over Syria.

In Ukraine, Moscow has also proposed humanitarian corridors out of besieged cities.

Zakaria Malahifji, a Syrian opposition official who was a political representative for Aleppo rebels in 2016, noted that areas of the city and other parts of Syria formerly in the hands of the opposition had been emptied of their populations.

"The Ukrainians must be cautious ... our experience shows this," Malahifji said, adding that he had conveyed his concerns to a friend at the Ukrainian foreign ministry.

Ahmed al-Sheikh, 26, watches news about the Russian invasion of Ukraine while sitting cross legged on a mattress on the floor of a school in Tadef that has been home to him and his family of 10 since they fled Aleppo in 2016.

His advice to Ukrainians: do not fight the Russians.

"Russia’s weapons are stronger, and no matter how many people get killed, Russia wants Ukraine."

(Additional reporting by Tom Perry, Maya Saad and Mahmoud Mourad in Beirut, Writing by Tom Perry; Editing by Mike Collett-White)