PHOTO

In the year 2000, China's Gross Domestic Product was around $1.2 trillion. Last year, it was $14 trillion--an increase of more than 1,000 percent in less than two decades.

The sheer scale of the rapid growth means the Asian giant must future-proof its energy requirements and find more fuel for the Dragon's fire, but is it using its flagship global Belt and Road Initiative to ensure those needs are met?

China, the second largest economy in the world, has obvious and rapidly burgeoning energy needs. The sharp growth in GDP over the last two decades has also coincided with the country's rise in global geopolitics and trade, transforming the Asian giant into the world's largest crude oil and gas importer. According to BP's Statistical Review of World Energy 2020 report, China was by far the biggest individual driver of primary energy growth in 2019, accounting for more than three-quarters of net global growth.

Driving the economic engine

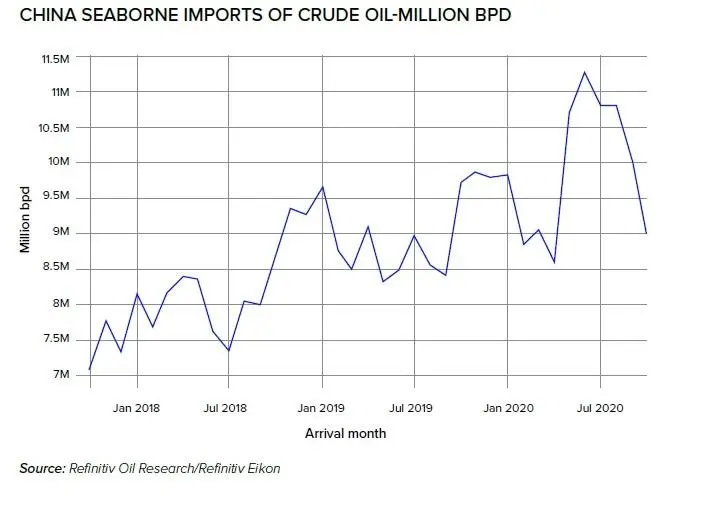

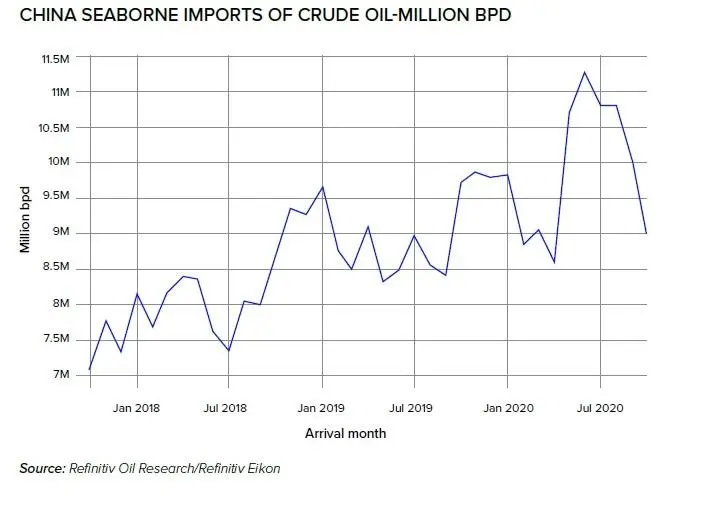

Oil plays an integral role in driving economic growth globally. With rising demand and falling domestic production, imports have climbed. Our chart on seaborne imports of crude oil shows a steadily climbing graph. Imports, which were at 7 million barrels per day in 2017, increased several-fold to a high of 11.3 million barrels per day in June 2020. This has also coincided with a rise in refining capacity in China over the last two years.

In 2019, about 72.5% of China's total consumption of crude oil was imported, according to a February report by news website Global Times.

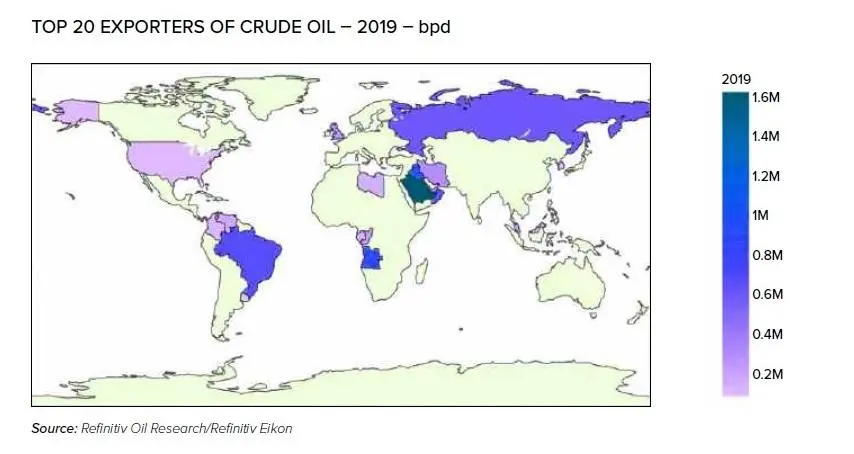

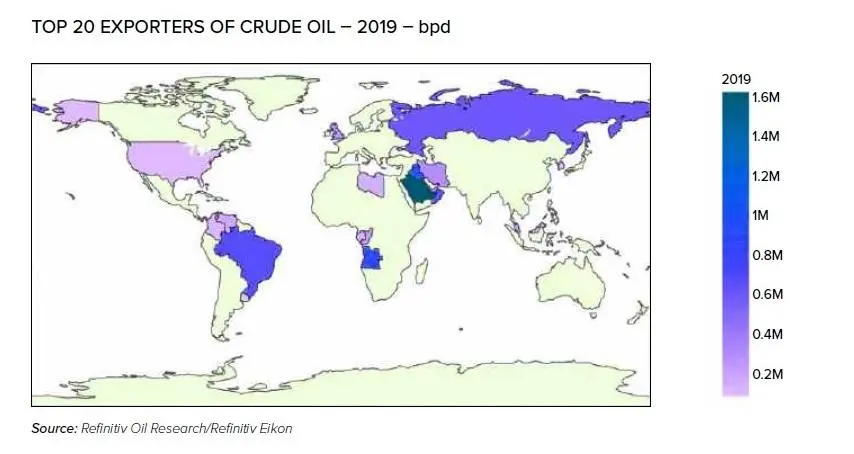

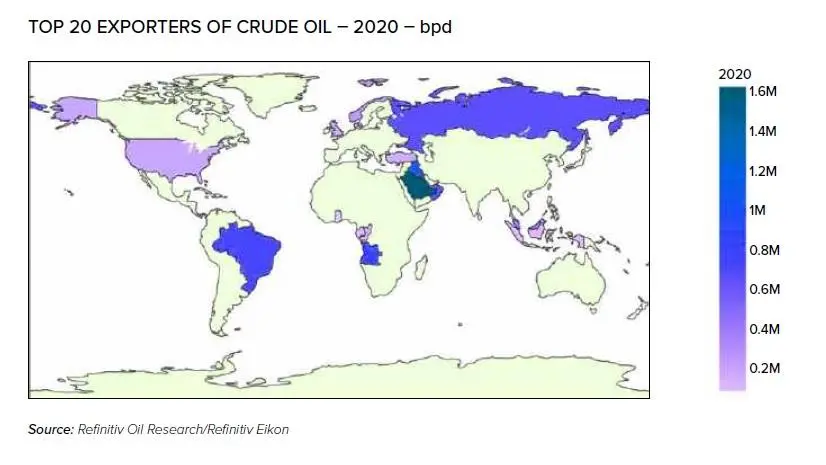

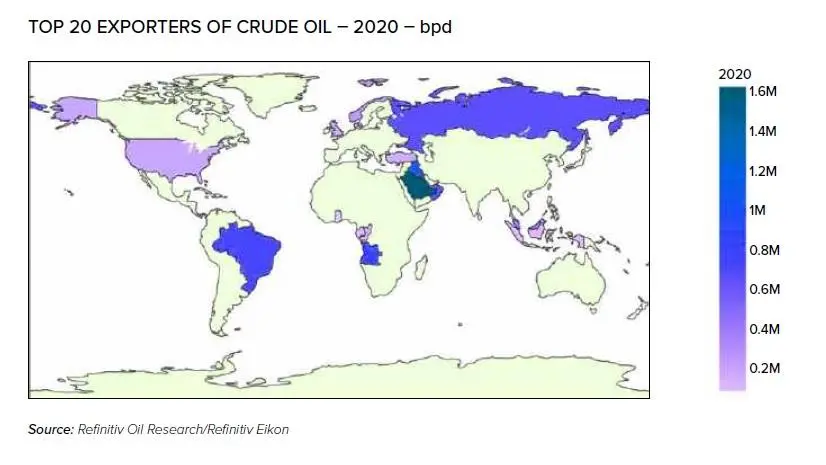

Apart from pipeline imports from Russia, China imports crude oil from almost all major oil-producing countries. The Top 20 charts show the global nature of sourcing by Chinese refiners. In some of these key destinations, China has also invested significant capital either through standalone investments or as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), possibly in a bid to ensure continuous and reliable access to oil.

NOTE: Under Refinitiv's BRI methodology, projects characterized as BRI Projects are those that require a signed memorandum of understanding or a joint statement of cooperation between China and the host country. The projects need to be disclosed on an official Chinese site, and if country-level agreements do not exist, by an officially recognized source in the host country.

Seeking cleaner energy

With rapid economic growth, policymakers in China have also had to come to terms with rising levels of pollution and the need to move towards cleaner-burning fuels. The government wants natural gas to comprise 15% of China's energy mix by 2030, up from 7.8% in 2018, to improve air quality and combat climate change. In September, Chinese President Xi Jinping told the United Nations General Assembly that China aims to be carbon neutral by 2060 and achieve a peak in emissions prior to 2030.

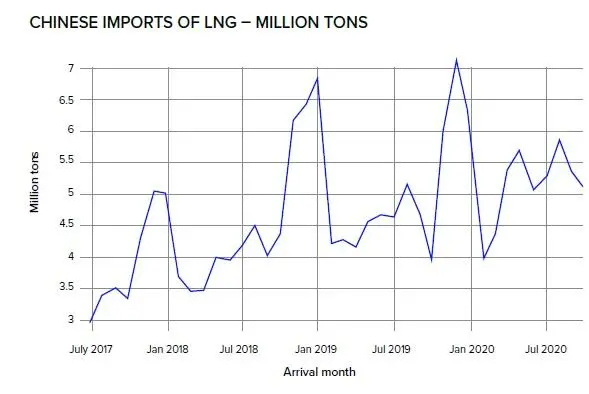

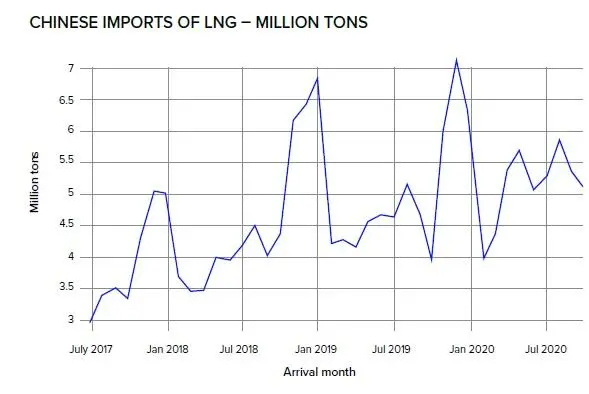

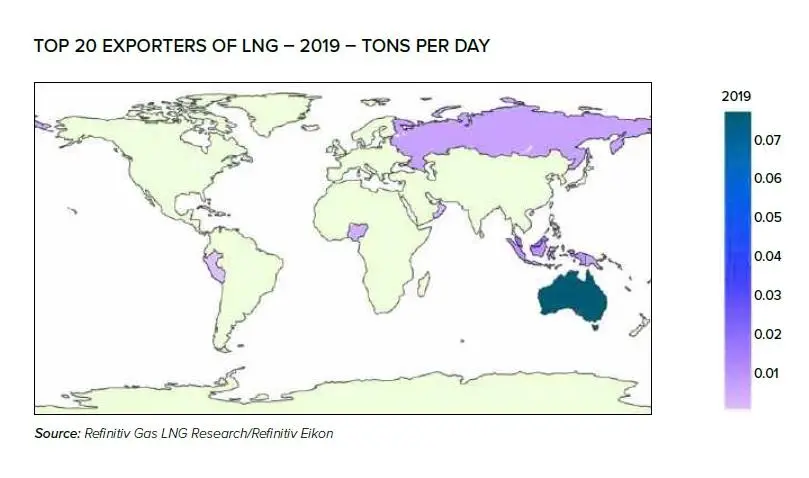

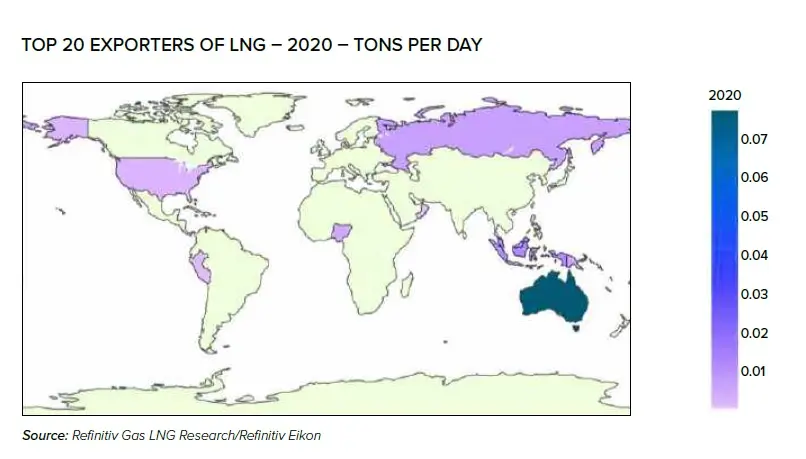

While the growing share of renewable energy sources are undeniable, a byproduct of the policy shift has been the increasing importance of LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas). Monthly imports of LNG into China have gone up from around 3 million tons in 2017 to about 5 million tons at present. Winter demand [December to February period] went up from 5 million tons in 2017 to around 7 million tons in 2019. Including LNG, China imports up to 45% of its natural gas requirements.

Unlike oil, where transport is relatively straightforward, LNG requires significant investments on the transport front. Globally, investments into LNG have gained pace in the last five years, bringing new exporters into the market and allowing for some level of diversification of supply. Between 2019 and 2020, the US has become one of the top suppliers of LNG to China, with the Sino-US trade deal providing a boost. Reuters reported that China more than trebled its LNG import volumes from the US in the first half of 2020.

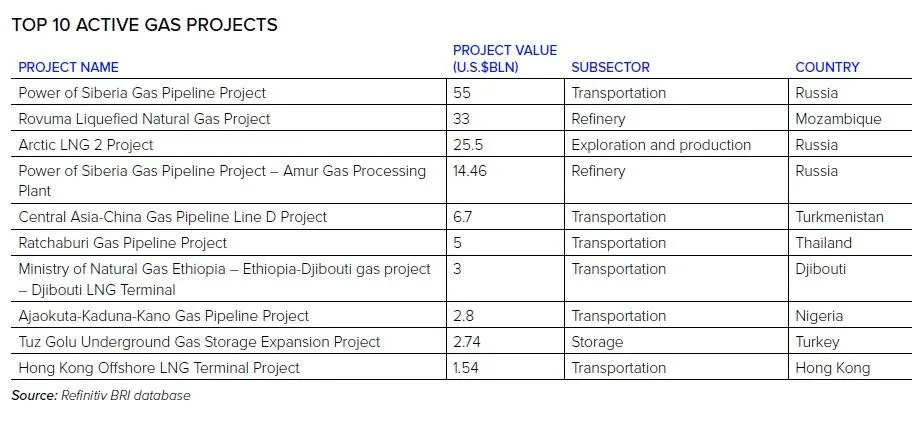

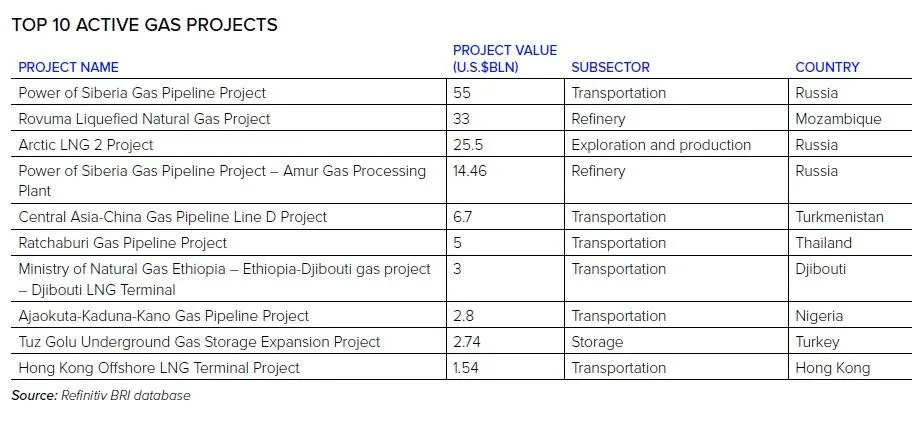

Oil and Gas projects in the BRI

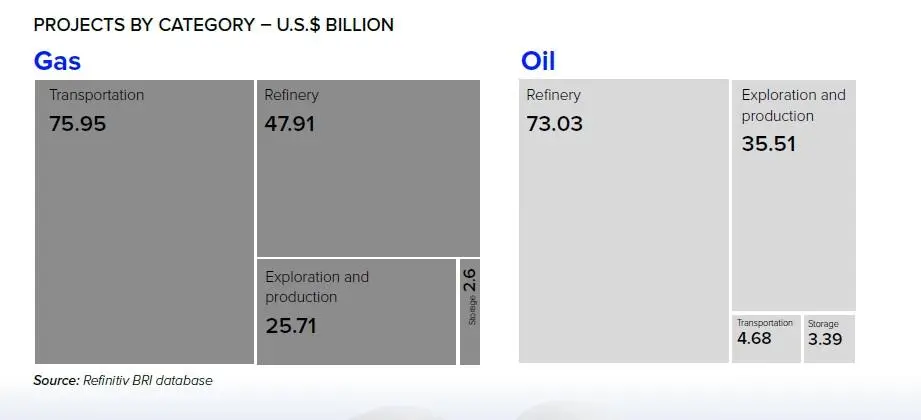

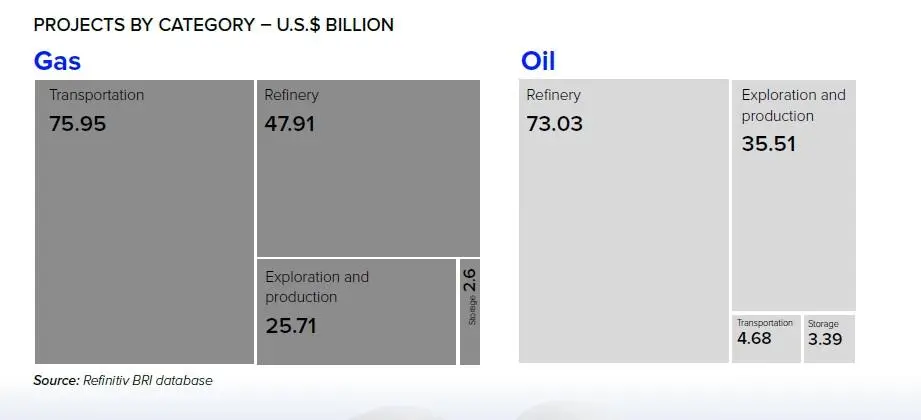

According to Refinitiv's BRI database, active BRI projects in the oil and gas space add up to about $270 billion spread out across different sub-sectors. Analysis of the project value split between oil and gas highlights China's growing focus on gas. A more in-depth analysis of the sub-sectors also underscores the difference in investment requirements between oil and gas.

Since gas is not easy to transport, of the $152.4 billion invested in gas projects, nearly 81.3% was accounted for by gas processing and transportation projects. Exploration and Production (E&P) accounted for only 16.9% of the total investment.

In contrast, the majority of the $116.6 billion worth of investments into oil have been into Refining (63%) and E&P (30%). Storage, transportation, and field support projects accounted for a marginal 7% ($8.1 billion).

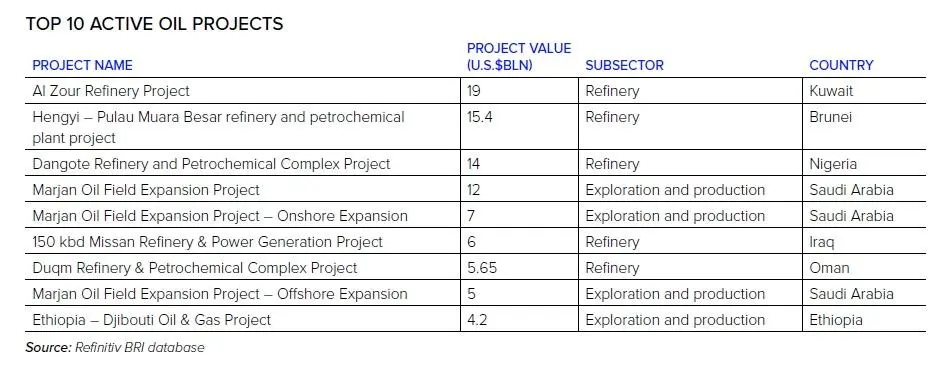

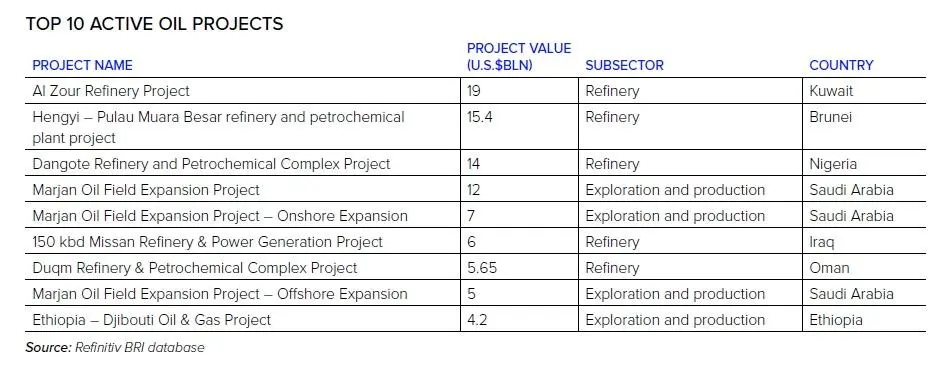

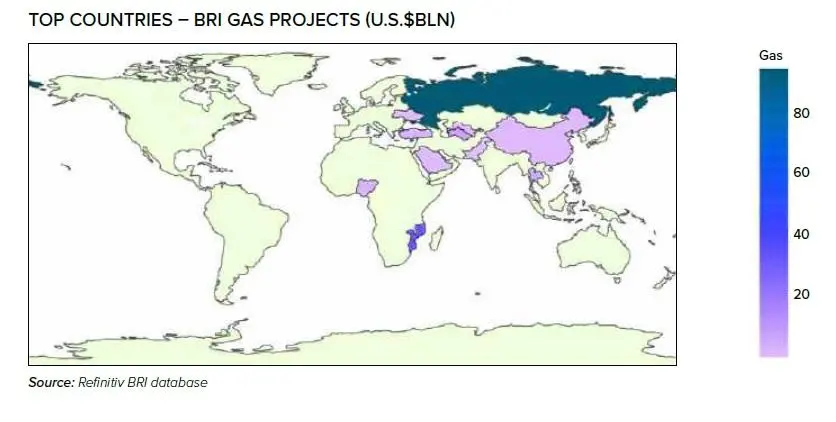

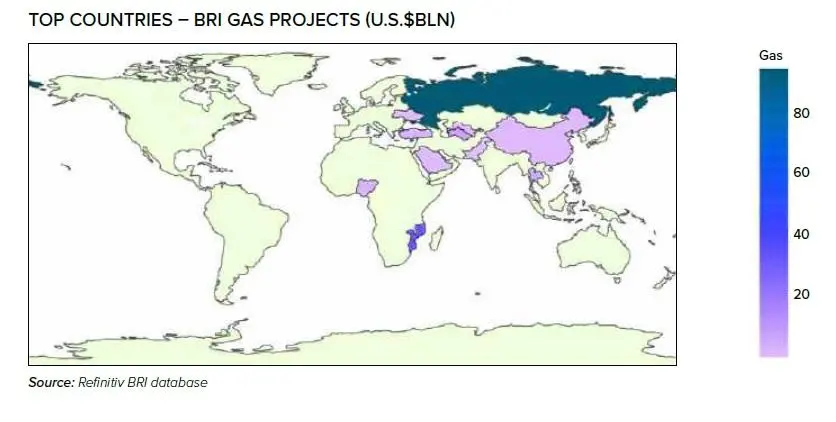

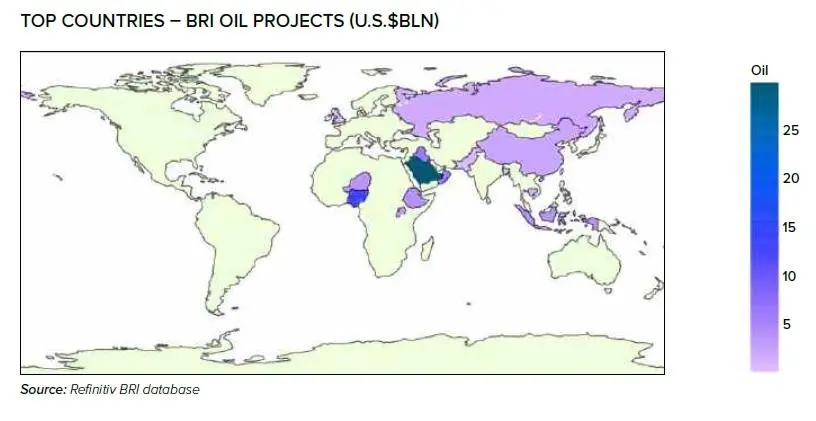

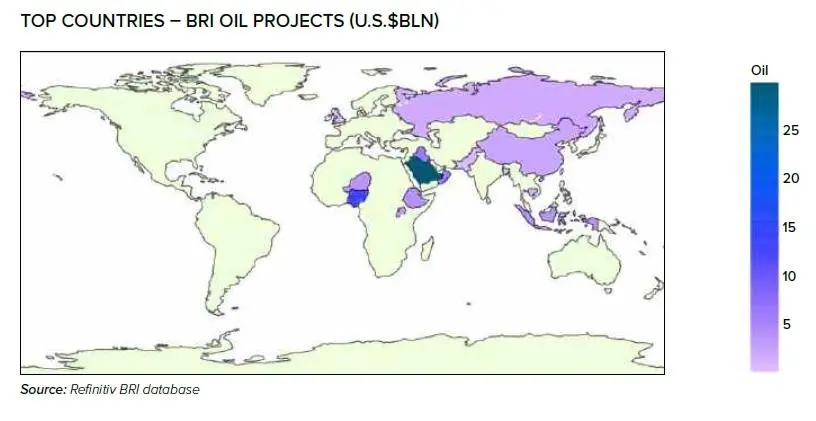

The Top Countries charts show the geographic footprint of oil and gas projects within the BRI. On careful observation, it may be seen that some of the countries where the projects have been planned are also countries from where a significant amount of sourcing of crude oil and LNG takes place or is expected to take place. For example, investments in the Rovuma LNG project in Mozambique could be construed as a step towards ensuring a presence in the Southern African nation where significant gas finds in the last decade have created hopes of a new player in the LNG space. Similarly, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Oman are all countries that export oil to China.

While not all investments aim towards securing an equity share in production, presence in these key exporter countries likely increases preference in exports. This, coupled with sovereign loans extended to producer countries and equity participation in projects, increases the reliability and security of energy supply needed to keep the Dragon roaring.

BRI'S OIL STORAGE OPPORTUNITY

When oil prices crashed, China was one of the earliest countries to capitalize on the cheap oil available in the market. In a market structure called contango, where the future prices of a commodity are significantly higher than the spot market prices, traders can effectively store the commodity and sell it in the future. During the process, they incur storage and financing costs but are compensated due to the higher selling price. Contango in the market is short-lived as more traders make use of it and are effective only when using inland storage, where costs to store are lower. In extreme cases, such as the one earlier this year, the contango could be large enough to allow the storing of oil in tankers.

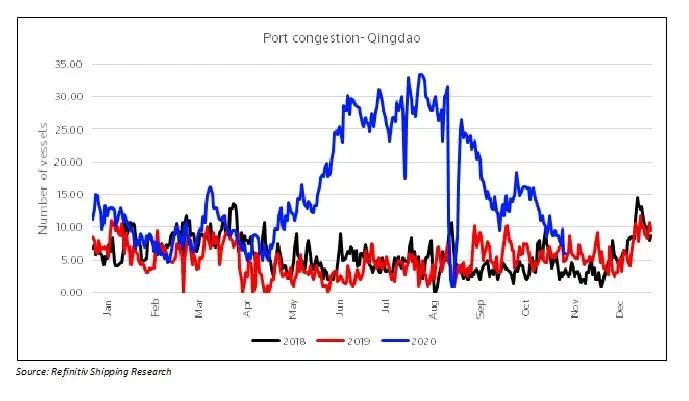

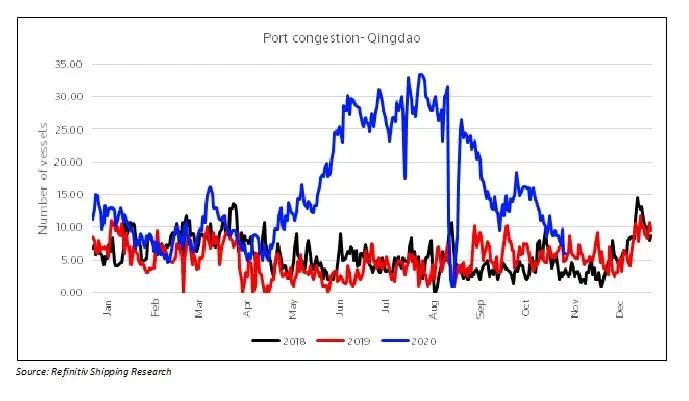

The chart on oil imports into China highlights that the cheaper crude bought by China in the second quarter made its way into the country through the late second quarter and third quarter 2020, creating record high imports. With the inland storages getting close to their capacity, several tankers had to wait outside Chinese ports for nearly months before getting to discharge the volume. The Port Congestion chart shows the congestion outside the port of Qingdao, reaching reached multi-year highs in the same period when imports started to go up to record highs.

Post-pandemic demand

The slowing of economic activity due to the COVID-19 pandemic has caused changes in global energy demand and supply patterns in 2020. In China's case, though, a rebounding economy in the second quarter coupled with cheap crude oil bought for storage helped drive up demand with crude rallying to to 90% of pre-COVID levels. Reuters reported that oil demand is forecasted to grow 2.3% to 13.6 million barrels per day in the second half compared to the same period last year, while natural gas demand is expected to grow at 4.2%. With China expected to be among the handful of economies posting growth in 2020, recovery of the global oil market will be in the hands of the Chinese, at least in the short-to-medium term.

(The author is Senior Analyst- Oil & Shipping Research (MENA), Refinitiv)

(This analysis was originally published in the 5th Edition of Refinitiv's BRI Connect Report, which can be downloaded here)

Disclaimer: This article is provided for informational purposes only. The content does not provide tax, legal or investment advice or opinion regarding the suitability, value or profitability of any particular security, portfolio or investment strategy. Read our full disclaimer policy here

© ZAWYA 2020