PHOTO

WASHINGTON - Weeks before the U.S. midterm elections, 65-year-old TJ Hughes got the news that rent on her Chicago apartment would rise by 80%, as prices for food and other essentials spiraled.

Hughes' only income is her government pension and her landlord's rental spike for her subsidized unit has led her to cut back on food – and to get political.

With an eye on the Nov. 8 vote, Hughes started mobilizing other renters to lobby local and state elected officials in northeastern Illinois to control rent increases.

"We've given them all of our concerns and issues, and now it's time for them to take action," she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. "We're trying to get them to meet with us before the election."

Soaring rents have prompted a national wave of tenant mobilizing in the United States amid the highest inflation in four decades, partly driven by housing shortages and two years of pandemic-related economic turmoil.

More than a third of U.S. households are renters, or some 44 million people, according to Harvard University's Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Almost 60% of renters saw their rent increase over the past year, found a June survey by Freddie Mac, a quasi-government housing finance company - prompting a surge in activism.

'I'M GOING TO VOTE'

Grandmother Sheila Nolan became a tenant organizer after her rent increased almost 10-fold earlier this year.

Nolan took a part-time job to support her granddaughter who lives with her in the southeastern state of Kentucky, only to be told that the employment made her ineligible for a government housing subsidy.

Nolan's monthly rent rose to $740 from $77, prompting her to quit the job and seek to get the decision reversed - but she is now months behind on her rent and worried about being evicted.

"I'm going to vote because, like I tell everyone, poor people just can't make it," said Nolan, 68, who lives in the city of Louisville.

Hughes and Nolan are part of the Homes Guarantee campaign, which is calling for federal protection for tenants, including rent controls, the right to renew their leases, to form tenants' unions and to repair their homes should landlords fail to do so.

The project is run by the People's Action, a national grassroots organizing network, which is urging President Joe Biden to take executive action on rent inflation.

The White House did not immediately respond to a request for comment though it last month announced new steps aimed at boosting finance for housing construction.

Nevertheless, Republicans are expected to win control of the House of Representatives and possibly also the Senate on Nov. 8, as polls suggest that voters trust them more than Democrats to tackle the most pressing issues - inflation and the economy.

'CENTRAL PAIN POINT'

Rent is the biggest expense for most poor and working-class families, and increases can be devastating, said Tara Raghuveer, a tenant organizer and Homes Guarantee's campaign director.

In recent weeks, the campaign has been knocking on an estimated 10,000 renters' doors in 26 cities to gauge experiences and drum up support.

"There is an intense focus on the rent as a central pain point when people are thinking about the economy," Raghuveer said. "And that is motivating some people to get involved in organizing other tenants."

Among renters who say rising housing costs have negatively affected their families, 58% say they are more politically active than they were two years ago, said Rob Warnock, a senior research associate with Apartment List rental platform.

"Increased political engagement among a coalition of renters could have the potential to swing elections, and the upcoming midterms could prove to be a turning point where such a movement gains momentum," Apartment List said on its website.

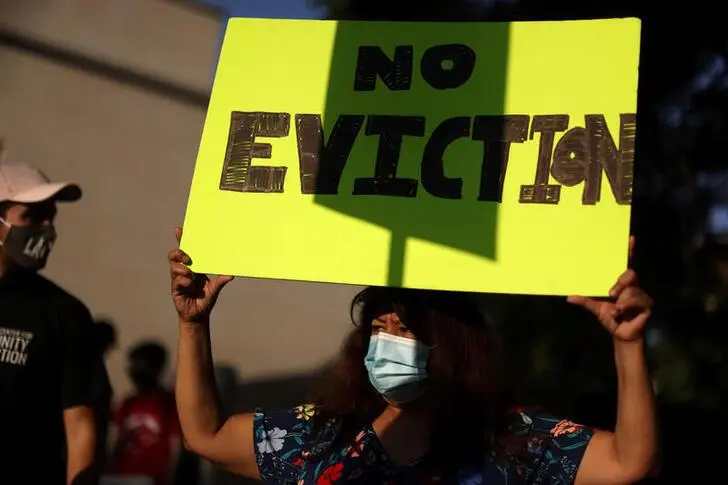

EVICTION CRISIS

The pandemic's economic turmoil doubled the number of households with rent arrears last year to 7 million - or 15% - according to the Urban Institute think-tank, but they were protected until August 2021 by a federal ban on evictions.

The U.S. government does not collect eviction data but Princeton University's Eviction Lab has recorded more than 1.2 million evictions in six states and 31 cities that it has been tracking since COVID-19 struck in March 2020.

"We're having a return of the eviction crisis in Virginia," said Marty Wegbreit, director of litigation with the Central Virginia Legal Aid Society, which helps tenants facing eviction.

More than 12,000 people were evicted in the southern state of Virginia in September, he said.

In the state's capital, Richmond, about 100 miles (161 km)south of Washington D.C., most tenants are paying more than 30% of their income for rent – and many are paying 50%, he said.

The state is seeking to head off evictions through a pilot program that helps pay for medical expenses or other bills, but that can only help so much, Wegbreit said.

"Until housing is elevated to at least the level of government support for other essentials such as food and health care, we'll continue to have an eviction crisis," he said.

The National Low Income Housing Coalition is tracking more than 50 ballot initiatives for Nov. 8 that could change state housing laws, for example by controlling rents and giving tenants the right to legal representation in eviction courts.

"Ballot initiatives have become an increasingly powerful and popular tool" for advocates, said Rasheedah Phillips, housing director with PolicyLink, a California-based research institute which seeks to advance social and economic equity.

"Rising rents paired with inflation has resulted in economic justice becoming a key issue for voters across political affiliation," she said.

"We can expect this to be a mobilizing issue for voters."

(Reporting by Carey L. Biron; Editing by Katy Migiro.)