PHOTO

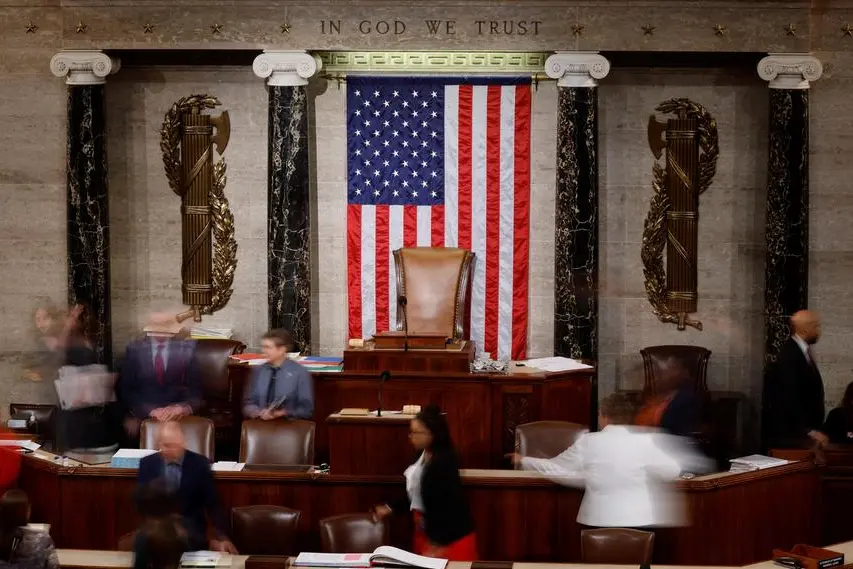

WASHINGTON, DC – Republican members of the US House of Representatives took more than four days and 15 rounds of voting to decide who would be the next Speaker of the House. Though the press coverage of this process was largely overblown – it was not a “crisis” or anything close to one – that does not mean there won’t be crises in the coming months.

Later this year, federal borrowing will bump up against its legal limit unless Congress can agree to raise or suspend the “debt ceiling.” If Congress doesn’t act, the federal government will not be able to issue new debt with which to honor all its financial obligations, such as interest payments to bondholders, salaries to soldiers, and benefits to Social Security recipients.

Raising the debt ceiling should be – and often has been – a routine matter. It does not authorize any new spending. Rather, it gives the executive branch the borrowing capacity it needs to honor existing spending commitments. It is Congress that decides on spending levels and tax rates, and when it sets federal spending higher than federal revenue, it implicitly determines the size of the budget deficit. Raising the debt ceiling merely allows for the borrowing that is needed to meet the obligations that Congress itself has created.

But that simple fact will not stop House Republicans from using the borrowing limit to try to force President Joe Biden and congressional Democrats to agree to federal spending cuts. The rabble-rousing Republicans who prolonged the House leadership election have made clear that a “clean” debt-ceiling increase – in which lifting the borrowing limit is not coupled with other measures – should not even be on the table, and Speaker Kevin McCarthy appears to have agreed to that condition.

The problem, of course, is that the weakness of McCarthy’s position in the House means he will find it very difficult to come up with a deal that satisfies this group of firebrands along with the rest of the Republican caucus. The Republicans need 218 votes for a majority, but they hold only 222 seats. McCarthy risks his speakership if he supports a deal that more than a handful of Republicans oppose.

Even brushing up against a federal government default would be a major market event. On the day before Republicans finally agreed to lift the borrowing limit during the 2011 debt-ceiling standoff, the S&P 500 was down 6% from its high that year. Three days later, S&P downgraded the United States’ credit rating, sending stock prices tumbling further.

The 2011 debacle sent economic confidence down to levels not seen since the 2008 global financial crisis. It also drove up interest rates, costing taxpayers $1.3 billion in 2011, according to the Government Accountability Office, with the Bipartisan Policy Center putting the cost at around $19 billion over a ten-year horizon.

While coming uncomfortably close to default would be bad enough, an accidental, temporary default would be even worse. And such accidents can indeed happen. In the spring of 1979, Congress reached a debt-ceiling deal at the last minute, but a subsequent computer glitch meant that the Treasury was late in making payments on maturing securities to individual investors and in redeeming Treasury bills. As a consequence, interest rates rose and taxpayers were on the hook for billions in additional payments. A computer glitch – or something similar – is a possibility this year, too.

The behavior of the chaos agents in the House, together with genuine uncertainty about the specific date on which the US Treasury would be unable to pay one of its bills, creates more risk of default than at any other time in decades. While it is unthinkable that the US would find itself in a period of prolonged default, it is entirely conceivable that Republicans and Democrats will fail to reach a deal before the deadline.

Were that to happen, we would be in the early stage of a global financial crisis. The Dow would plunge by thousands of points per day, and the credibility of the US – its trustworthiness as a country that pays its debts on time – would be substantially eroded. After a day or two of this chaos, a clean bill to increase the debt ceiling would pass both houses of Congress with overwhelming bipartisan support. Republicans would have accomplished nothing.

How can this unnecessary crisis be averted? The first step is to throw out any plans that depend on the House firebrands playing ball. They aren’t bluffing. Biden and congressional Democrats need to accept this reality and start working on a deal today. They should acknowledge the more widely shared Republican argument that federal spending has reached problematic levels – a conviction founded at least partly on the American Rescue Plan’s role in sparking inflation – and they should then find some spending that can be cut. In exchange, the debt ceiling should be raised high enough that it will be many years before it can again be used as a weapon.

Second, responsible members of Congress must make plans to avoid a default. One idea worth exploring is to use a discharge petition to force a debt-ceiling increase to the floor of the House in the event that McCarthy is unwilling to do so. Democrats may be reluctant to do this, because it would likely garner few Republican votes; but they need to be willing to put political considerations aside. Another possibility is that McCarthy could bring a debt-ceiling increase to the floor over the objections of the rabble-rousers, knowing that it would likely cost him his speakership. Like the Democrats, he, too, should be willing to put the country’s welfare first.

All responsible politicians must get to work immediately, with the goal of raising the ceiling this winter. The closer we get to the as-yet-unknown day this summer when the government will run out of borrowing power, the worse the market reaction will be.

Congress is playing with fire. Its members are supposed to be statesmen, putting responsible governance ahead of other considerations. More of them need to rise to the occasion.

Michael R. Strain is Director of Economic Policy Studies at the American Enterprise Institute.