PHOTO

Amid all the brickbats thrown at one of the longest bull markets in history, the remarkable buoyancy of world equity prices may simply be down to a shortage of shares.

Trade wars, an unpredictable White House, a messy Brexit and rising interest rates have all failed this year to knock stock markets off their collective perch for very long. Wall Street indices are at record highs and global equity benchmarks are less than 4 percent from the year’s peaks.

For many, the most basic laws of supply and demand help square that circle.

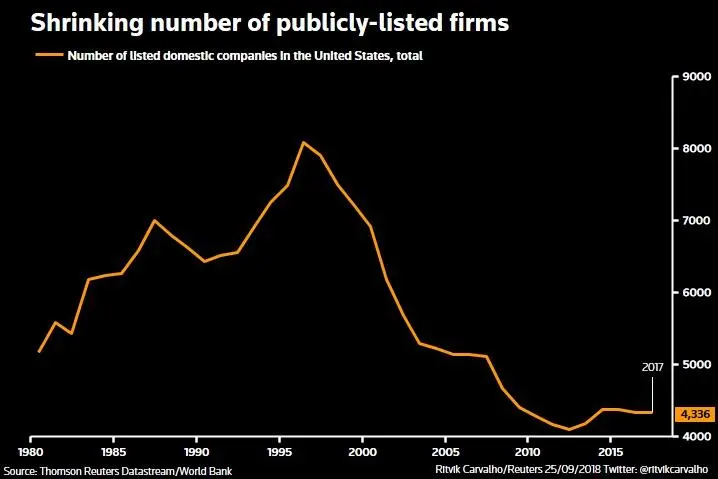

Equity markets worldwide are slowly shrinking. Not enough shares are being issued to offset those being withdrawn from circulation and net equity supply turned negative in 2016 for the first time ever, according to JPMorgan which expects low to negative supply this year after a marginally positive 2017.

Even just assuming stable investor demand for equity investments going forward, the supply picture means more money on aggregate will be chasing every public share.

Fewer stocks are being sold via initial or secondary public offerings while buybacks, cash-funded mergers and acquisitions and even de-listing of companies altogether drain the world of investable equity.

From January through August this year, primary listings added shares worth around $126 billion, Thomson Reuters data shows. Even after allowing for secondary listings and share placements to employees, issuance volumes should be dwarfed by buybacks, which may surpass $1 trillion this year.

Few expect the trend to reverse soon, with some citing overall disillusionment among company bosses with the vagaries and the glare of the marketplace as well as the relative cheapness of alternative debt financing.

“It is a pain being listed on the stock market, there’s red tape, short-termism, excessive scrutiny - these are all issues. But the really basic issue is, companies will go where the money’s cheapest,” said Robert Buckland, the Citi strategist who dubbed the trend “de-equitisation” as far back as 2003.

While de-equitisation has been around a while, it gathered pace during the period of near-zero rates when rock-bottom capital costs led companies to tap debt markets instead of selling equity.