PHOTO

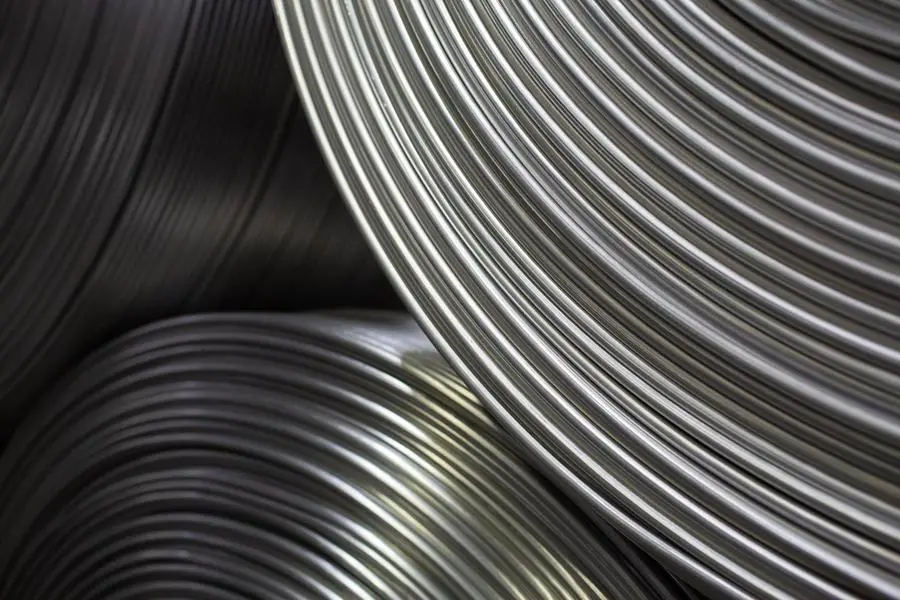

When Presidents Yoweri Museveni and William Ruto jointly broke ground for the Devki Mega Steel Plant in Tororo on November 23, the images carried more meaning than ceremonial politics.

At $500 million, the Narendra Raval-financed facility is one of the most significant industrial undertakings in East Africa in recent years. But its deeper significance lies in what it represents — a return to the logic of regionalism, shared prosperity and coordinated industrial strength.

For years, the East African Community (EAC) has spoken of integration while often stumbling over competing national ambitions.

A project of this scale — financed by a Kenyan billionaire, located in Uganda, and supplying markets across the bloc — is a rare reminder that regional industrialisation is not only possible, but essential. It is how the region begins to build bargaining power on a global stage increasingly shaped by size, scale and manufacturing muscle.

President Museveni’s insistence on banning unprocessed mineral exports is a bet on long-term industrial capability rather than short-term revenue.

President Ruto’s open support signals a shared commitment to strengthening regional value chains that benefit both countries. This is, in many ways, the kind of project that defined the old East African Community.

When the first EAC took shape in the 1960s, its planners — for all their flaws — understood the power of comparative advantage. Uganda, blessed with cheap power from the Owen Falls Dam, was the logical home for regional steel production, a role cemented by the Madhvani-owned East African Steel Corporation (Easco). Kenya and Tanzania focused on complementary functions, creating a balanced industrial ecosystem in which no single country duplicated the other’s high-cost industries.

The Tororo project should be a lesson in not repeating those mistakes. Political backing for such investments is both natural and necessary, but it must not morph into the familiar pattern of patronage, protectionism and vested interests.

East Africa needs more billionaire-led bets of this kind: capital-intensive, export-oriented, and regionally integrated. But even more, it needs the discipline that once guided the EAC’s early industrial design — a commitment to comparative advantage, rational location of industries, and genuine economic cooperation.

If East Africa is to speak with a stronger voice internationally, it must first learn to act with coherence at home. Tororo offers a promising template. Whether it becomes the rule, rather than the exception, will depend on whether leaders choose regional logic over domestic political calculus.

© Copyright 2022 Nation Media Group. All Rights Reserved. Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (Syndigate.info).