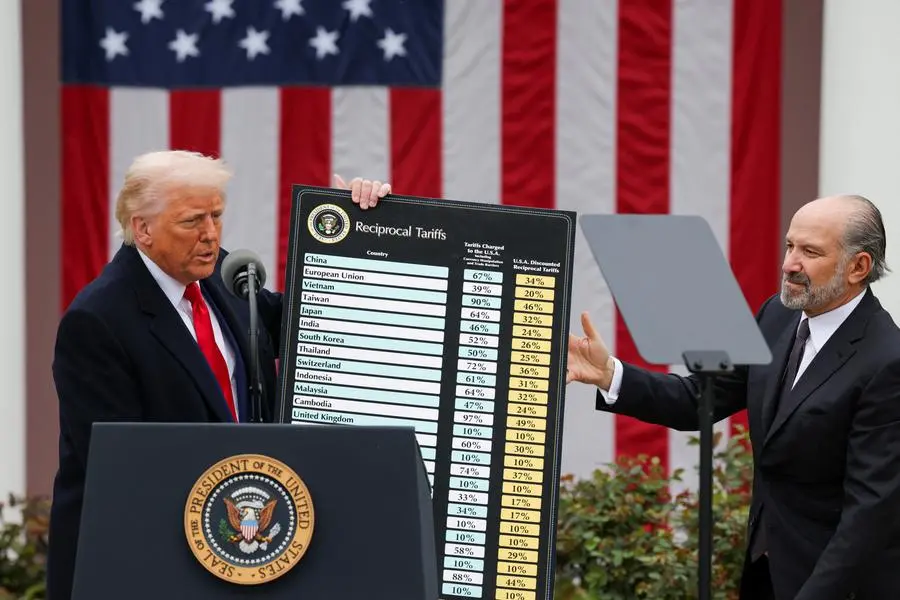

PHOTO

LONDON - An irony about the ludicrously steep import tariffs U.S. President Donald Trump imposed on China last month is that they made no sense as taxes - at least if you believe one of the canons of Republican tax policy.

The rapid reduction of those bilateral import levies in Geneva this weekend - after less than a month in place - may thus owe much to what some economists dub the 'Tariff Laffer Curve'.

The controversial theory suggests government revenue from higher taxes peaks at a specific tax rate, above which damage to the incentive to work, economic activity and investment starts to depress the overall tax haul. The reverse was also true, it argued, and this was used to justify tax cuts even when budgets were tight.

The idea, one of the key tenets of Ronald Reagan's economic adviser Arthur Laffer in the 1980s, was used to help justify the decade's rollback of tax and government in America and Britain. The theory's detractors claimed the revenue-boosting powers of tax cuts were never proven and merely acted as a smokescreen for 'trickle down' economics.

But Laffer's curve and his ideas have remained popular with successive Republican administrations. Laffer himself, now aged 84, has been a Trump supporter and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Trump in 2019.

Assuming that tariffs, Trump's favored trade weapon, are in fact a tax and designed to be a revenue-raising function, then some economists argue the draconian 145% tariffs levelled at China far exceeded what any Laffer Curve would deem sensible.

In other words, if 100%-plus U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports and vice versa started to act as a bilateral trade embargo, then the revenue-raising aspect of the levies would obviously be weakened.

To some degree, that was acknowledged by U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent in Geneva on Monday when he said neither side wanted a trade embargo.

And with China reporting a 21% drop in bilateral trade in April and cargo data from U.S. ports showing Chinese container activity plummeting another 35-40% last week, an embargo was, for all intents and purposes, starting to play out.

TARIFF LAFFER

To what extent revenue calculations will factor into the global tariff strategy moving forward remains to be seen, but they will likely play an important role in budget negotiations unfolding in Congress this month. And eventual bilateral trade deals being worked out bear watching in that regard.

Benn Steil, director of economics at the Council on Foreign Relations, last month outlined three major problems with reliance on steep tariff hikes for government revenues.

"The first major problem is that tariffs at these unprecedentedly high levels will likely push us beyond the apex of the tariff 'Laffer Curve' - the point at which tariffs bring in declining revenues owing to the steep fall in imports."

Another reason, Steil argued, was that to boost government revenue via tariffs Americans needed to keep importing and not substituting for American-made goods - the other stated aim of the trade policy. The third reason was that the higher risk of recession would erode broader tax revenue by far more than tariffs could muster.

Economists Simon Evenett and Marc-Andreas Muendler delved into the implications of the 'Tariff Laffer Curve' in a research paper published last month.

When tariffs increase, they wrote, they discourage the taxed activity - trade. "The relevant empirical question is: at what import tax rate do tariff revenues max out?"

The economists considered a range of cases where each dollar of import taxes collected reduces the trade deficit by anywhere between 25 and 90 cents. They concluded that even in an extreme case where U.S. savings only go up by 25 cents on the dollar of tariffs collected, the maximum gain in government revenue is under $500 billion - less than four weeks of federal spending.

The total U.S. tax take last year was $4.92 trillion. Trump's plan to roll over expiring tax cuts passed during his first White House term would reduce revenues by about $5 trillion over 10 years, according to a congressional estimate.

"Hiking import tariffs is not a viable solution to fund today's public finances," they concluded.

That the gambit on extreme Chinese tariffs appears to have been cut short so quickly may speak to the thorny budget negotiations underway this month, negotiations on tax cuts that neither projected tariff revenues nor federal spending cuts appear to be justifying.

If Trump truly needs import tariff revenues to square the circle, he will have to be more careful in setting them so as not to bite the hand that feeds.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters

(By Mike Dolan; Editing by Nia Williams)

Reuters