PHOTO

A top Indian opposition politician was expected to fight his arrest in court Friday in a case supporters say is aimed at sidelining challengers to Prime Minister Narendra Modi before next month's election.

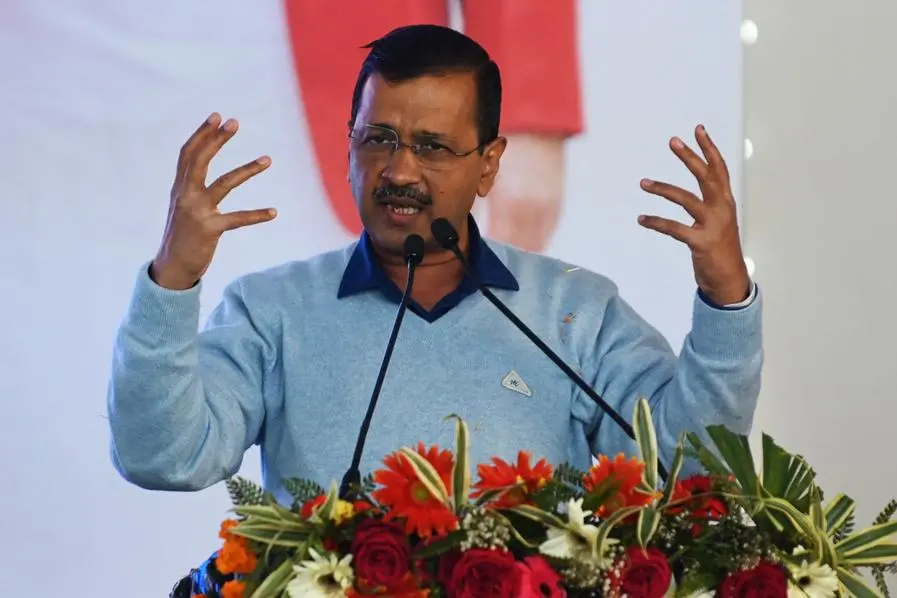

Arvind Kejriwal, chief minister of the capital Delhi and a key leader in an opposition alliance formed to compete against Modi in the polls, was detained on Thursday in connection with a long-running corruption probe.

He is among several leaders of the bloc under criminal investigation and one of his colleagues described his arrest as a "political conspiracy" orchestrated by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The Supreme Court said it would hear a plea challenging the legality of Kejriwal's arrest on Friday by lawyers for his Aam Aadmi Party (AAP).

Police were out in force in front of the BJP's Delhi headquarters where they had erected barricades in anticipation of AAP's call for public protests against the arrest.

Kejriwal's government was accused of corruption when it implemented a policy to liberalise the sale of liquor in 2021, ending a lucrative government monopoly.

The policy was withdrawn the following year, but the resulting probe into the alleged corrupt allocation of licences has since seen the jailing of two top Kejriwal allies.

Kejriwal, 55, has been chief minister for nearly a decade and first came to office as a staunch anti-corruption crusader. He has resisted multiple summons from the Enforcement Directorate to be interrogated as part of the probe.

Delhi education minister Atishi Marlena Singh said Thursday that Kejriwal had not resigned his office.

"We made it clear from the beginning that if needed, Arvind Kejriwal will run the government from jail," she told reporters.

- 'Decay of democracy' -

Tamil Nadu chief minister M.K. Stalin, a fellow member of the opposition bloc, said Kejriwal's arrest "smacks of a desperate witch-hunt".

"Not a single BJP leader faces scrutiny or arrest, laying bare their abuse of power and the decay of democracy," he said.

Modi's political opponents and international rights groups have long sounded the alarm on India's shrinking democratic space.

US democracy think-tank Freedom House said this year that the BJP had "increasingly used government institutions to target political opponents".

Rahul Gandhi, the most prominent member of the opposition Congress party and scion of a dynasty that dominated Indian politics for decades, was convicted of criminal libel last year after a complaint by a member of Modi's party.

His two-year prison sentence saw him disqualified from parliament for a time until the verdict was suspended by a higher court, but raised further concerns over democratic norms in the world's most populous country.

Kejriwal and Gandhi are both members of an opposition alliance composed of more than two dozen parties that is jointly contesting India's national election running from April to June.

But even without the criminal investigations targeting its most prominent leaders, few expect the bloc to make inroads against Modi, who remains popular a decade after first taking office.

Many analysts see Modi's reelection as a foregone conclusion, partly due to the resonance of his assertive Hindu-nationalist politics with the members of the country's majority faith.