PHOTO

LONDON - It may seem odd to have a central bank boss clinch a rare soft landing of the U.S. economy and then face the sack - but that very real possibility has many investors fretting about potential post-election risks to Federal Reserve independence.

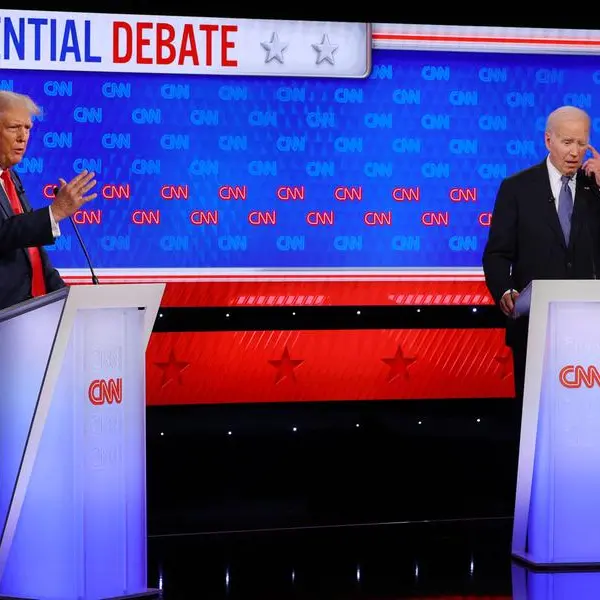

Several banks have recently delved into claims by former President and Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump - neck and neck in opinion polls with incumbent Joe Biden - that if he's elected in November he would not reappoint Jerome Powell on the expiry of the Fed chair's term in 2026.

And even though many downplay the ability of the White House to politicize Fed monetary policy per se - they acknowledge investor concern about the pressure and suggest even a change in style and tone with a new Fed boss might bear close watching.

Trump himself appointed Powell in 2017 but then quickly turned on him in a series of public broadsides as the Fed continued to push up interest rates through 2018 despite his pleas for the opposite - branding him "clueless" at one point.

And last month the ex-President insisted again that he would not reappoint the 71-year-old Powell, while complaining that any rate cuts over the coming months would be merely designed to boost the Democrats in an election year.

The Wall Street Journal reported last weekend that Trump's team was already discussing three possible replacements - former Fed governor Kevin Warsh, former Council of Economic Advisers chair Kevin Hassett and former Ronald Reagan guru Arthur Laffer, known for his controversial take on the relationship between taxes and government revenues.

While it all remains in the realm of speculation - and another finely-balanced White House race is still eight months away - it's a delicate moment for the Fed and central banks at large given the bruising two-year fight they've just mounted against the post-pandemic inflation spike worldwide.

Even though inflation is subsiding back toward 2% targets in most major economies, investors are now highly sensitive to where it settles longer-term given that a recession, in the United States at least, looks to have been avoided in the disinflation process.

Without mentioning the United States or the Fed specifically, International Monetary Fund chief Kristalina Georgieva said on Thursday that multiple elections around the globe this year was a good moment to underline the importance and the success of central bank independence historically.

"Risks of political interference in banks' decision making and personnel appointments are rising," she wrote in a blog on the IMF website. "Governments and central bankers must resist these pressures."

Although the IMF has its remit packed with many developing economies in where independence is frequently blurred, the combination of high inflation and high debts is hardly the preserve of emerging markets alone - nor it seems are struggles to keep inflation management at arm's length from government direction.

Georgieva said governments' adherence to their own sound budgeting and debt control was also critical to allowing central banks function without influence.

"Enacting prudent fiscal policies that keep debt sustainable helps to reduce the risk of 'fiscal dominance' — pressure on the central bank to provide low-cost financing to the government, which ultimately stokes inflation."

RUBBER STAMPS

How much of the debate around post-election Fed risks is already jarring investors is harder to parse.

Morgan Stanley's chief global economist Seth Carpenter, who spent 15 years working at the Fed, cited multiple client queries about Fed independence in the runup to the election - but said there was no evidence or experience to doubt the Fed's insistence that it stands aloof from the electoral cycle.

"What happens after the election is a different story," he added.

New appointments to the Fed chair or board can have an impact in communications or dissent on policy, wrote Carpenter, even though the institution was well insulated.

The next presidential term only had two Fed board vacancies due anyway, he added, far short of any majority.

One safegaurd in the extreme event of the White House attempting to install a "rubber stamp" Fed boss was the fact the Federal Open Market Committee picks its own chair by the letter of the law - even if by convention it defers to the chair of the Fed board that's picked by the President and Senate.

"A new Fed chair could very well shift the FOMC's reaction function at the margin," he added. "But the institutional process is designed to guard against the extreme case of a Fed that is directed by the White House instead of the dual mandate."

How would markets react anyway if they were worried by either direct public pressure to keep rates low - or indeed a fresh fiscal expansion that forced the Fed to hang back due to worries about the Treasury market or wider financial stability?

Long-term market inflation expectations, for one, may start to climb again. Already, 10-year measures of these remain 30-50 basis points above 2% Fed targets - but they have remained around those levels for the past year and other risk premia in bond markets remain under wraps.

Barclays currency strategists point out that the first Trump presidency was associated with repeated calls for lower interest rates alongside a tax-cutting fiscal expansion -- but the Fed resisted and hiked rates anyway, much to the chagrin of the then President.

However the more inflationary post-pandemic world raises the bar on any policy inaction going forward, they reckon.

"A scenario in which the Fed follows a fiscal expansion path is more obviously inflationary than in 2016," they concluded. "In so far as this leads to a steeper U.S. curve, it would likely also result in dollar weakness, all else equal."

All hypothetical at this early stage of course - but markets may not hang about as opinion polls ebb and flow into November.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters

(Editing by David Evans)